Danube,

the Calm Water of Bratislava Lido

Anna Kidová

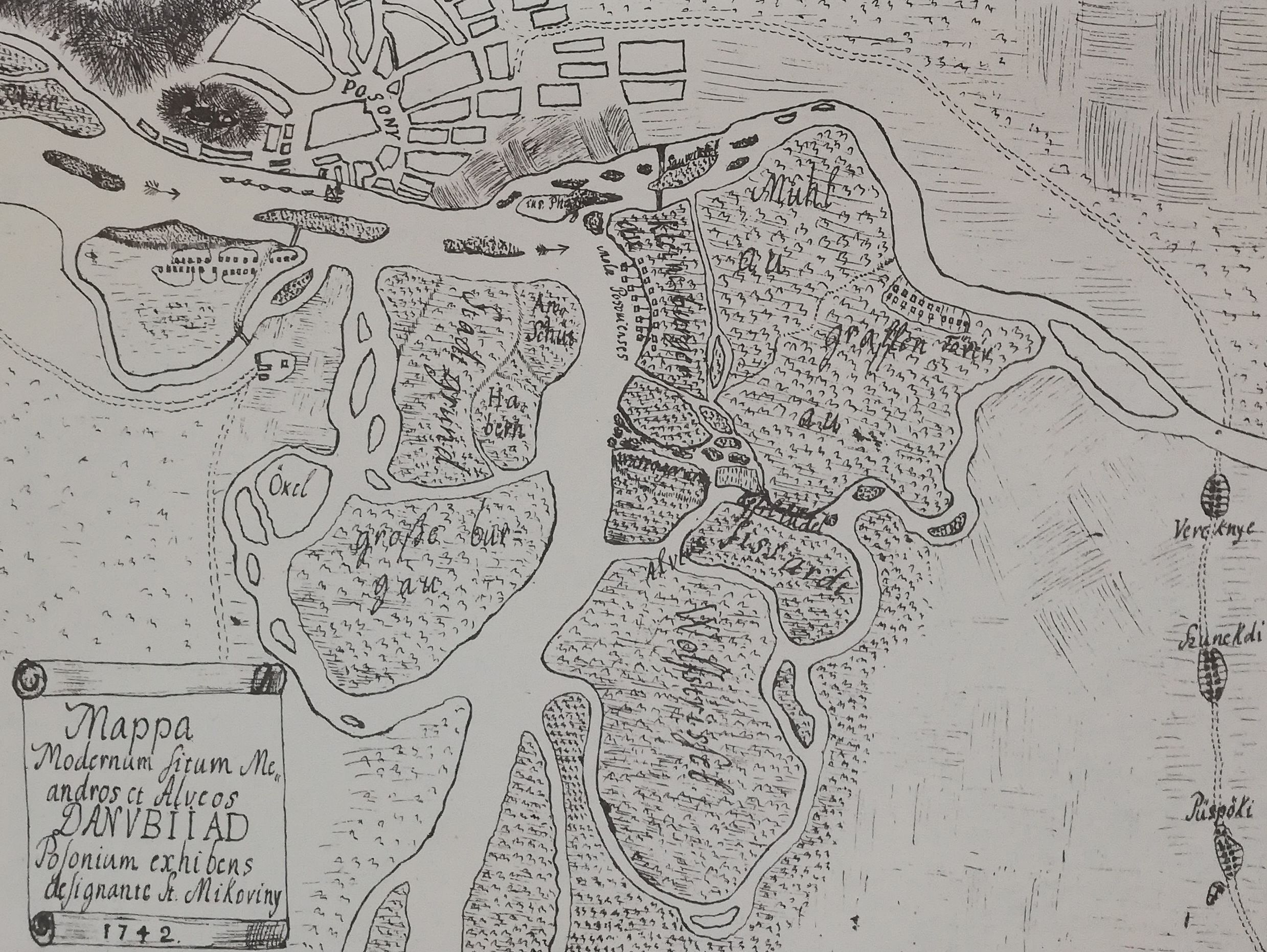

I don’t know anyone who would question the majesty of the Danube Riverbed, and the elegance and grace with which the water flows and washes its diverse banks. This fascinating European river artery springs from the Schwartzwald, flows through dozens of countries and after almost three thousand kilometers, empties into the Black Sea. The upper section of the central Danube flows through our territory from the mouth of the Morava River up to the mouth of the Ipeľ River. On its transition from the Vienna Basin to the Danube Lowland, it flows on a concentrated riverbed with a significant slope. It grandiosely enters the environs of Bratislava through the Devín Gate of the Little Carpathians, where it maintains a relatively large slope and effortlessly flows on its own extensive alluvial cone of quarterly sediments consisting of layers of gravel and sand from 12 to 20 meters thick. From the Devín, the character of the Danube is the same, but near the municipality of Palkovičovo its slope suddenly changes. The invisible and constant work of the water suddenly appears in the daylight from under its surface. The energy of the water drops with the slope and stream load, which it brings along all the way from Donau-Auen, Austria, and deposits in the riverbed, creating an obstacle for ships and boats. Ensuring a continuous transport route in the past century required significant human intervention into the functioning of the river’s natural processes. This need was preceded by significant damage to the national economy caused by extensive floods. Although anti-flood protection on the Danube was mentioned as far back as the times of King Béla IV (1267), the beginning of more complex efforts to prevent the uncontrolled overflowing of its banks didn’t begin until the 18th century when the land between Bratislava and Gabčíkovo was afflicted by destructive floods. Samuel Mikovíni also participated in the implementation of anti-flood projects, and elaborated engineering designs for the reconstruction of dikes, especially in the inundated territory of the river’s Žitný ostrov(Rye Island) (1726). At that time, the Danube’s system of branches was a dynamic entity particularly in times of high water. The map of Bratislava County depicts the Danube Riverbed near Bratislava laterally branching out in an anastomosing (multi-channel) type of channel (Fig. 1). Up to 1830, Žitný ostrov was protected only by simple dikes. The anti-flood system was built through its entire territory, but proved to be ineffective against the floods in the 1850s up to the 1870s which caused extensive damage. The original more-or-less unified water flow in at least six large meanders (Fig. 2) turned into a wide and unstable riverbed with several alluvial deposits. Up to the present, the Danube River is lined by protective earth dikes in our territory, representing a reminder of insufficient protection during the catastrophic floods of 1954 and 1965 (bursting the dyke near the municipalities of Patince, Klúčovec and Kolárovo, Fig. 3). These relatively unsuccessful attempts to control the Danube waters were followed by the decision to resolve the flooding issues at the government level in Czechoslovakia and Hungary. The agreement between these countries on the construction of the Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros dams (1977) comprehensively addressed the anti-flood protection of the territory, the effective use of its energy potential and the provision of a shipping route. The wild Danube had finally been tamed! But at what cost to the original ecosystems and land diversity? The complicated situation of villages afflicted by floods is easy to understand, but it is very difficult to imagine the loss of the original character of the country or even to try to quantify it. After the Danube’s branches were cut off from the main riverbed in the 1950s until the late 1980s, the branches were annually filled for two to three weeks by surface water when the flow rate was higher than 4,000 m3.s-1. According to the Slovak-Hungarian agreement, in recent years water flows of 400 - 600 m3.s-1 are released into the old riverbed during the vegetation period. However, these flows do not at all resemble the original strength and ability of the water to follow the path of least resistance. During simulated floods, the water spills over its banks only locally and this stagnant or slowly flowing water does not run off; nor does it transport and subsequently deposit materials such as stream loads, floating solids and decomposing organic matter in the form of detritus and debris. These natural processes are out of balance, and the territory, which was originally characterized by dynamic changes, has became relatively static. Although the issue of the impact of floods on the lives of people in the area has been resolved, the natural component of the country had to adapt to completely new conditions, and the biotopes of many communities had to transform their life strategy or become extinct. The symbiosis of the original species with the flood pulse system was no longer possible. Thus, the regular floods naturally supported the dynamics of the biotic components of the alluvial ecosystem. Their diversity primarily depends on the diversity of abiotic conditions. Dynamism is one of the attributes of an alluvial ecosystem. The function of natural floods lies particularly in the connection of the riverbed and its direct surroundings, spilling out to the plains. Such naturally distributed flows distinctively affect internal riverbed processes related to erosion, transport and the accumulation of sediments, the transformation of the channel pattern and the eco-stabilization function. In this context, we can observe the alluvial forests lining the Danube’s banks in Bratislava. They have adapted to this well-functioning cooperation for centuries. The alluvial forest in the Lido area is no exception (Fig. 4). Among others, this is reflected in its retention capacity and ability to process floods and to slow the runoff. Such alluvial forest territories are also important from the perspective of energy flows, the exchange of nutrients and the conservation of original communities of biotopes. These relationships work both ways. Organic matter in the water supports the proper functioning of the water’s ecosystems and vice versa. The periodicity of floods maintains the communities on the plain in a productive state.

The developer’s plan would most probably block the natural interaction of the alluvial forest with the Danube riverbed, as we still remember it from 2013 (Fig. 5). The current problems of Bratislava “County” are no longer related to protecting the health and property of people from floods. Attention has shifted to the values of the natural “islands” which have been preserved near Bratislava despite massive regulations. The values of scientific knowledge of the natural environment and the interest of a developed society in following the further development of Lido as a natural laboratory have come to the fore. Understanding the ecological significance of an original alluvial forest and its direct connection to this river of European importance definitely adds a new dimension to the discussion about its future.

Fig. 1. Small-scale map made by Samuel Mikovíny, anastomosing

(multi-channel) riverbed of the Danube near Bratislava of 1742.

Fig. 1. Small-scale map made by Samuel Mikovíny, anastomosing

(multi-channel) riverbed of the Danube near Bratislava of 1742.

Fig. 2. Course of the Danube Riverbed from the Devín Gate to the Hungarian border on the map of Bratislava County from the 18th century.

Fig. 3. Danube flood in 1965, municipality of Kolárovo.

Fig 4. Transformations of Bratislava Lido in the last two centuries. (Source: www.staremapy.sk)

Fig. 5. View of flooded Lido near the Apollo Bridge during the flood in 2013. Photo: Ľuboš Pilc, Pravda. (Source: https://spravy.pravda.sk/domace/clanok/282765-snimky-z-vrtulnika-ako-sa-rozlial-dunaj-pri-bratislave/)