HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF BRATISLAVA LIDO

Peter Szalay

Architect Solà-Morales uses the term terrain vague to refer to abandoned, residual, undefined places that have lost their original function, yet remain places of identity where the past and present meet.

Bratislava Lido is a typical terrain vague; despite its central location, it has a peripheral character. It comprises a mixture of rural development, brownfields, sporting grounds, garden cottages and undisturbed nature. Although its urbanization has been discussed since the beginning of the last century, no plans have been implemented. This area remains terrain vague for mainly prosaic reasons, such as a shortage of resources and unresolved ownership relations. However, the lack of clarity about what to do with it is another factor.

In the first half of the 1900s, recreation and sports played a significant role in the planning of this area, similar to the intentions which led to the founding of the nearby park, today’s Sad Janka Kráľa (Janko Kráľ Park) in the middle of the 18th century. It became a place for mass recreation, as the Lido public pool, docks as well as number of sports stadiums were located there.

In the second half of the 20th century, plans to establish a new city center on the right bank of the Danube were proposed. During the socialist era, the city grew significantly, particularly as a result of the extensive planned development of mass housing. The Petržalka housing estate, the most extensive mass housing project in Czechoslovakia, was created in the vicinity of this territory. The conventional concentric conception of city construction development has been maintained since the time when a grandiose international competition was held in 1967. Urban planners and architects consider this territory as the most valuable area for the construction of a modern city center.

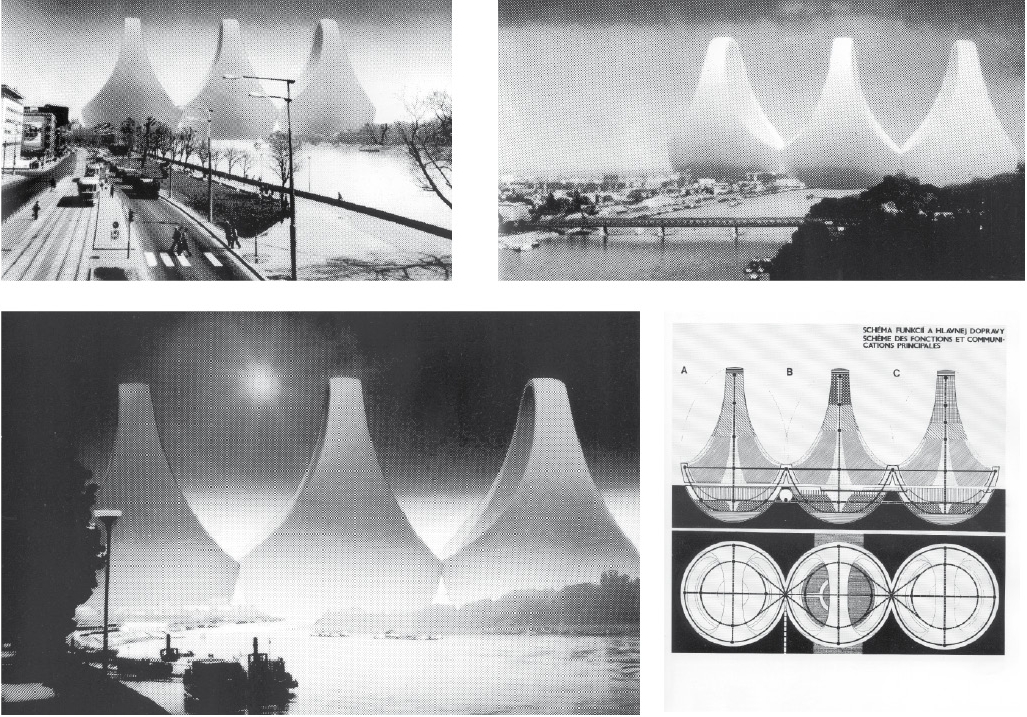

The Istroport plan, conceived by the VAL group in 1972, straddled the borderline of architecture and art. It was a utopian project that envisioned the shifting of construction activities from the banks of Danube to the river itself. However, environmentalists and conservationists, who had mobilized to block the planned construction of the large dam further down river, had other ideas. However they failed to prevent its implementation. Due to the dam construction, the river bed was deepened and the dam itself minimized natural variations of the water level, which during the summer droughts created Lido’s sandy beaches and negatively impacted the natural biotopes. The Soví les nature reserve was declared in 2010 on part of this territory in an attempt to conserve the precious biotopes of alluvial forests of European and national significance. This was the first time that the natural values of this territory were officially acknowledged and became the subject of public discussion.

The Lido pool on the river bank closed in the 1990s and sports activities of the majority of the populace of Bratislava were reduced to the use of the bike path on the Danube embankment. The most massive campaign concerning this territory began in 2017 when J&T and HB Reavis, Bratislava’s largest developers, launched their “New Lido” campaign. Although their project is in principle based on plans formulated during the socialist era, they employed innovative marketing strategies to inform the government and the general public of their intentions. However, in 2017 they failed to be granted significant investment status which would have simplified the permit processes and enabled the expropriation of land.

Water sports enthusiasts who had docks there were especially opposed to the plan, as it would significantly transform the bank. In response to these objections, the investors implemented some small adjustments to the plan and promised to leave space for non-motorized boats and a beach. These discussions marked the most recent proposal presented to the general public, and the official approval process is ongoing.

Strategic map of city shelling by French army, 1. 6. 1809.

Source: Bratislava Lexicon of Topography

Section from the Mikoviny map of Danube around Bratislava, 1742. Territory of Bratislavské Lido characterized by alluvial (flood plain) forest with

regular rhythms of flooding,

border of firm soil and Danube

and its branches.

Section from the Mikoviny map of Danube around Bratislava, 1742. Territory of Bratislavské Lido characterized by alluvial (flood plain) forest with

regular rhythms of flooding,

border of firm soil and Danube

and its branches.source: Bratislava City Archive

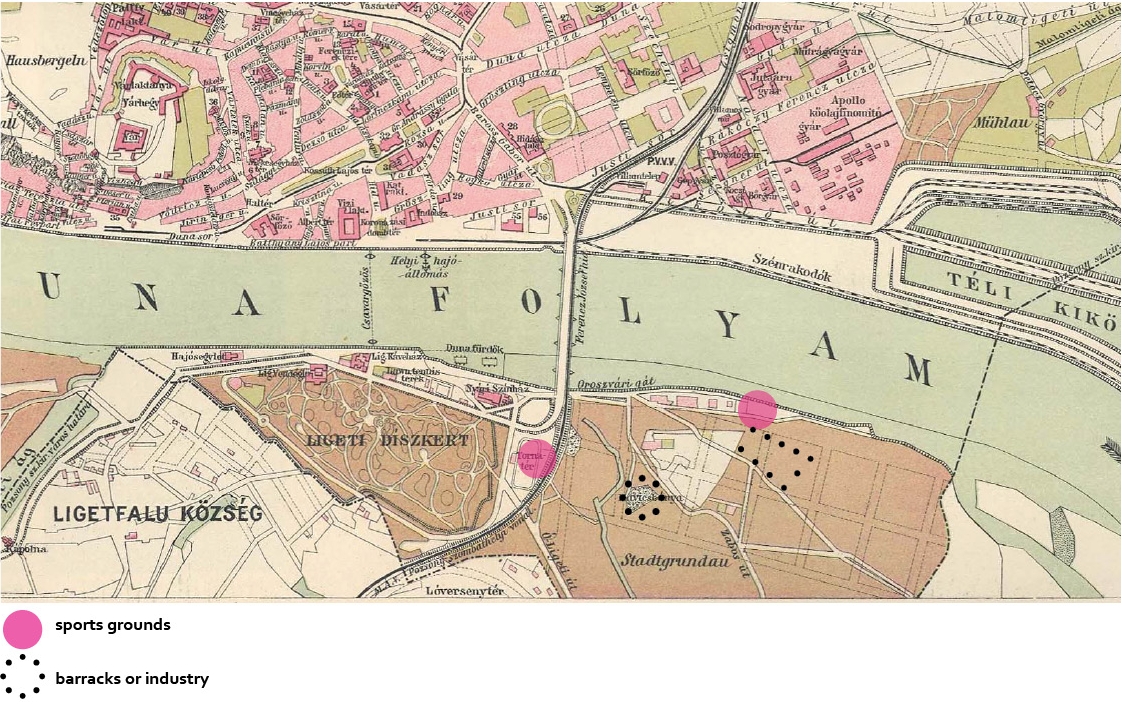

Section from the map from 1912 with marked preparation of waterfront expansion as well as the planned streets of the area called Stadtgrundau. Apart from its sports infrastructure, which was concentrated on the reinforced waterfront, the area also had a gravel quarry.

Source: Bratislava City Archive

Floating swimmingpool

Source: Bratislavské rožky

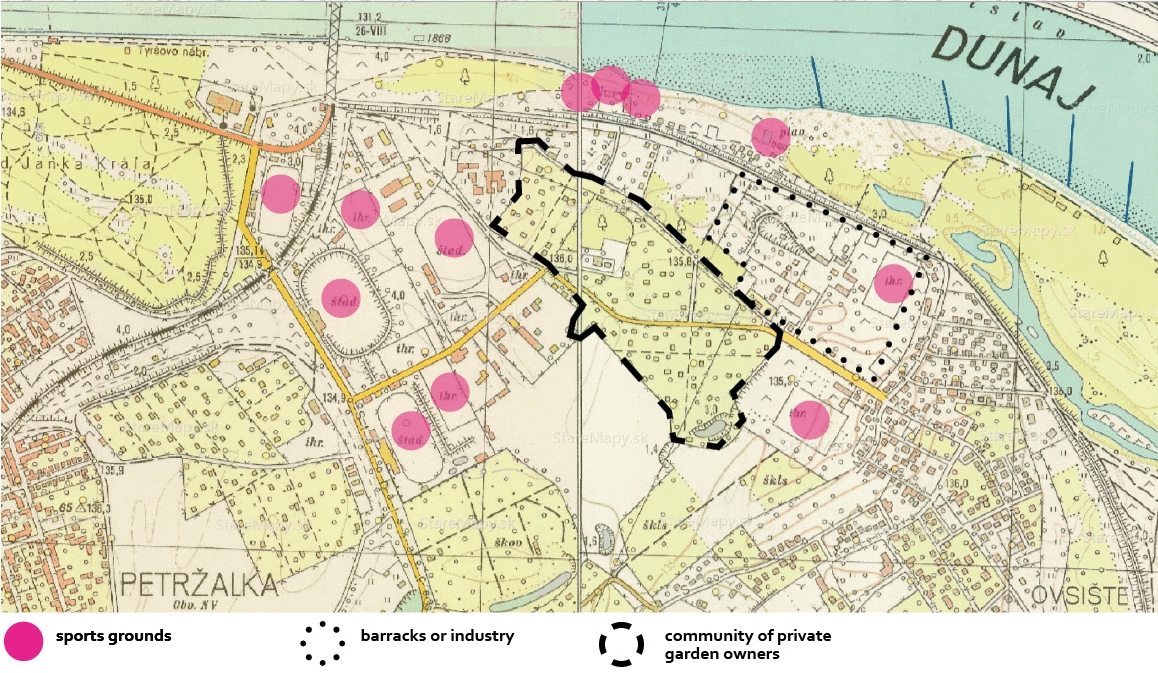

Secction from map of Bratislava, 1939. The recreational use of the area was strengthened towards the end of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy and in the interwar period.

Makkabea sport stadium, Friedrich Weinwurm, 1935.

source: Bratislava City Archive

Petržalka, 1967.

Source: Archive of architecture, oA, IH, SAS

Photo accompanying an article on the tender for the construction of the southern precinct of Bratislava - Petržalka, 1966.

Source: Journal Projekt, 1966

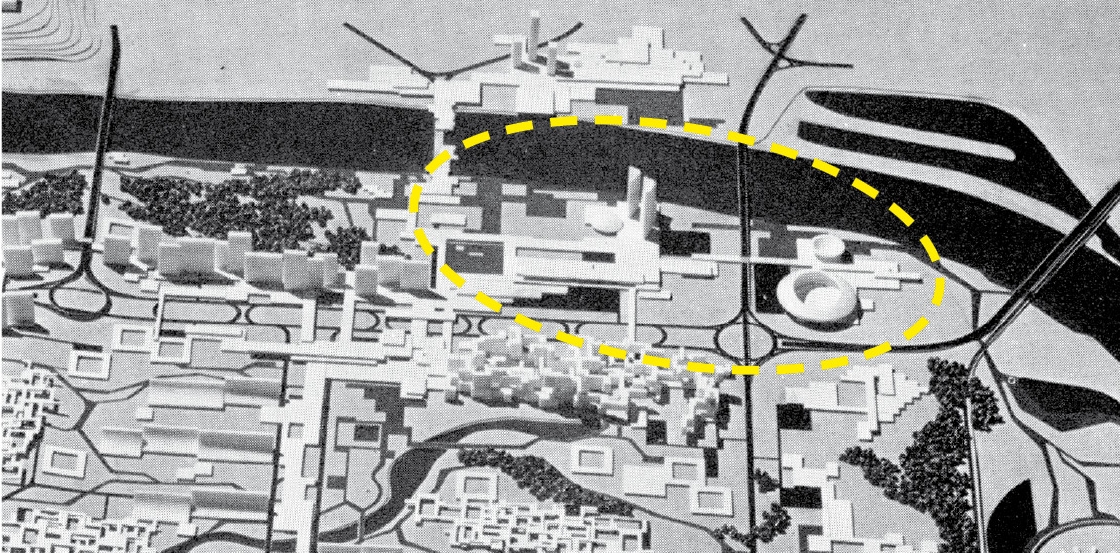

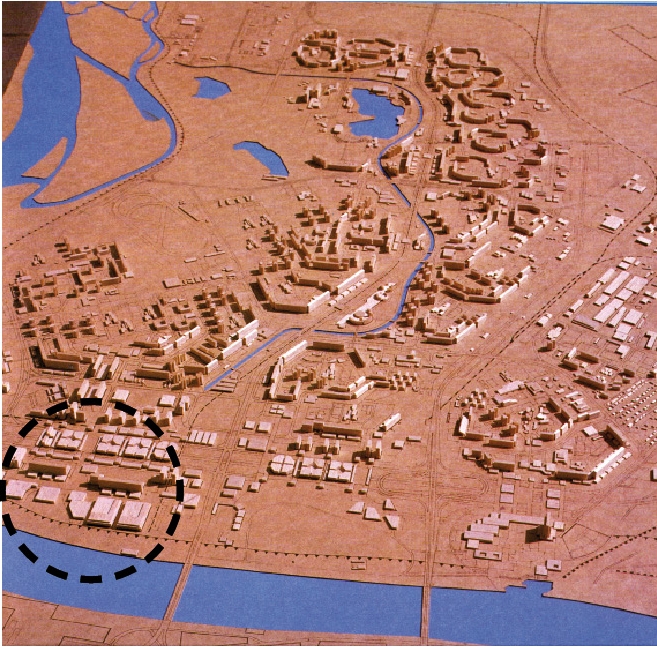

Model of the competition proposal for Petržalka, 1967, authors: Alexy, Kavan, Trnkus. Lido area as the “center of the right bank” of Bratislava.

Source: Archive of architecture, oA, IH, SAS

Istroport, VAL, 1972, authors: Mlynárčik, Mecková, Kupkovič. Utopian proposal of the architecture-artistic group for a megalopolis for

120 000 citizens on the Danube.

Source: Archive of architecture, oA, IH, SAS

Model plan of development of the Petržalka, Stavoprojekt Bratislava, 1985. The plan was an addition to the town planning scheme, and called for the development of the area.

Source: Yearbook of Stavoprojekt, 1989

Sections of Bratislava map, 1986

Source: Archive of architecture, oA, IH, SAS

The Gabčíkovo dam and the Hrušov reservoir were built in late 1980s and early 1990s despite the opposition of ecologists. One of the effects of the damming of the Danube was the stabilization of the water level in Bratislava. As a result, the beaches which appeared on the banks of the river during summer droughts remained under water, and made swimming by natural beaches impossible.

Source: TASR

Bratislava in 2005

Developed territorial plan of the Petržalka Central City, MARKROP, 2012.

Source: www.uzemneplany.sk