Insect Monitoring at the

Lido Site

Marek

Semelbauer

Introduction

The urban environment has long been on the radar of natural scientists. The evidence that the number and diversity of insects are dropping, particularly in the cultural landscape, has been growing. Modern industrial agriculture is most frequently considered the main culprit, but not all of the segments of the landscape are equally affected by the loss of biodiversity; there are still refuges and one of them is the urban landscape. Cities and municipalities comprise approximately 4% of the area of Slovakia. This does not seem like a lot; however, since only slightly more than 2% of the landscape in Slovakia is in the 4th and 5th levels of protection, the contribution of cities and municipalities to biodiversity may be essential.

At first glance, the results of biodiversity research in the city show that the biodiversity of pollinators may be higher there than in the surrounding open landscape. Some studies have even reached the conclusion that it is higher or comparable to that in protected areas. Bees are particularly successful in cities. The warm urban microclimate and mosaic-like environment suit them. Moreover, bees do not mind frequent grass mowing, since their nests are most often located underground or in dead wood. Butterflies, on the other hand, are very sensitive to mowing, which is why in cities the butterflies dependent on wooden plants and very mobile species such as several species of monarchs are more successful.

New Lido incorporates an alluvial forest, old solitary trees, areas with scarce disconnected vegetation and an embankment with meadow vegetation, all within a relatively small area which would indicate that this can be an interesting area from an entomological perspective.

Methodology

The monitoring of insects took place in 2021 from April to early October, the vegetation season. The site was visited in six monthly intervals.

Pollinators were mapped through three methods. Butterflies, bumblebees, orthopterans and some other species of insects distinguishable in the field were monitored through the use of the modified trans-sectoral method, in which the mapping agent walked along a pre-established route and noted the relevant species and their numbers. We also placed 5 yellow bowls on two spots (near the Apollo Bridge on the ruderal area and in the vicinity of the solitary trees on the other side of the bridge), usually at least for 5 hours. Insects were captured individually, by searching the relevant microhabitat (dead wood, sap stream, areas of vegetation and dirt exposed to the sun) or by sliding through herbaceous vegetation.

The following dominant groups of pollinators were monitored: butterflies (Papilionoidea); from the Hymenopterans order: bees (Anthophila), scoliid wasps (Scoliidae) and thread-waisted wasps (Sphecidae); from the Dipterans order: hoverflies (Syrphidae), thick-headed flies (Conopidae), bee flies (Bombylidae) and robber flies (Asilidae); and certain distinctive species from the Orthopterans order.

The following sources were used for determining species: butterflies: Macek et al. (2015), bees, thread-waisted wasps and scoliiidae: Macek et al. (2017), orders of bees and leafcutting bees: Amiet & Krebs (2012), hoverflies: van Veen (2004), thick-headed flies and bee flies: van Veen (2020), robber flies: Wolf et al. (2018), orthopteran: Kočárek et al. (2015).

Results

We recorded a total of 352 insects classified in 6 orders and 98 taxons, in particular, 24 species of butterflies, 32 species of Hymenopterans, 31 species of Dipterans and 2 species of beetles. In addition to insects, 3 species of reptiles and one species of Notostraca were also recorded at the location.

Butterflies (Papilionoidea)

Butterflies were represented primarily by the ordinary and prevalent species typical for mesophile meadows and alluvial forests. The large copper butterfly (Lycaena dispar), which is prevalent in Western Slovakia and is not endangered, a species of European importance, was also found. The most common meadow species include the common blue (Polyommatus icarus) and meadow brown (Maniola jurtina) butterflies.Sightings also included the comma (Polygonia c-album) and lesser purple emperor (Apatura ilia), typical species for alluvial forests.

Hymenoptera

Several interesting bees were recorded from the Hymenoptera order, such as Anthidium septemspinosum and the wool carder bee (Anthidium florentinum); they are thermophilic species, which in western Slovakia are located close to or directly on the northern border of their habitat. They are large and relatively easily recognizable. The males of both species are territorial and can be found in the vicinity of larger flower clusters which are used by females as the source of nectar and pollen, in particular, vetches for Anthidium septemspinosum and clusters of Echium and bugloss for Anthidium florentinum the another interesting couple is Nomiapis diversipesand its cuckoo, the White-spotted Red Cuckoo Bee Pasites maculatus. Nomiapis diversipes is relatively prevalent in the warm areas of Slovakia, but in the Czech Republic it is an extinct species, like the P. maculatus. I have found both species in several locations in Bratislava, but the P. maculatus occurs only individually.

Epeolus tarsalis has been perhaps the most significant finding. Like P. maculatus, it is a cuckoo and has recently been found in Europe, primarily on the Atlantic coast and in the Netherlands and France. Except for one finding from Sandberg (National Nature Reserve Devínska Kobyla) in 2018 (Bogusch & Hadrava 2018) no findings have been recorded for the past 50 years. Thus, the specimen from Lido represents only the second recent finding from Central Europe.

Two not original, but large and distinctive species from the Sphecidae family were found here: the Mexican grass-carrying wasp (Isodontia mexicana) and the yellow-legged mud-dauber wasp (Sceliphron caementarium). Both species are common and rapidly expanding.

Diptera

The robber fly (Dasypogon diadema, Asilidae) was definitely the most distinctive fly; this species is on the red list in Germany and the Czech Republic as strongly endangered or vulnerable, but it seems that it is relatively prevalent in Bratislava. Almost 3 cm in size, the adults are predatory and hunt predominantly for bees, which is not typical for predators. Predators are usually opportunistic; they hunt for the most accessible prey they can find. Thus, the presence of Dasypogon diadema shows that there is a sufficient number of prey – bees at this site which can be assessed as a positive signal. Holopogon fumipennis (Asilidae) is another interesting species that is endangered in Germany. It lives in an open environment and prefers dry and warm undergrowth with tall herbs and the presence of solitary trees.

Caliprobola speciosa and Sphiximorpha subsessilis, two very interesting species from the Syrphidae family, are found here. Caliprobola speciosa is one of the largest and most beautiful hoverflies in Slovakia. Its larva is found on decaying roots or wet hollow cavities located low on tree trunks. This rare species that prefers uplands is considered endangered in the Czech Republic and Spain.

Sphiximorpha subsessilis, strongly endangered in Germany and endangered in the Czech Republic, is considered as a retreating local species at the European level. Its larvae depend on a special microhabitat - sap streams primarily on poplars and elms, which are especially prone to its production. The stream is colonized by bacteria and other microorganisms which the larvae feed on. The adult hoverfly very convincingly imitates solitary wasps and is one of the most beautiful examples of mimicry in our wildlife. Both species were found directly on solitary trees right next to the Apollo Bridge.

B. bicolor, B. insensilis and B. maculipennis, three hoverfly species of the Brachyopa genus are found on sap streams, and the alluvial forest along the Danube River. All 3 species are considered rare in Hungary and more or less endangered in the Czech Republic and Germany.

We need to mention the unspecified thick-headed fly of the Conops (Conopidae) genus. Since I was not successful in a closer specification of this species according to the available key, it could be considered as unknown in the territory of Slovakia.

Beetles (Coleoptera)

2 species of Meloidae beetles. both protected, are found at Lido: Mylabris variabilis and Epicauta rufidrosum. It is interesting that E. rufidorsum was only known in Slovakia from older collections from the 1950s, but it is back. This might be due to the warming of the climate and construction development in the surroundings of Bratislava, as construction temporarily creates area of naked dirt with thin herbal and abundantly blooming vegetation. Such locations have a very warm microclimate and are suitable for various species of grasshoppers. The larvae of Meloidae beetles feed on the eggs of certain larger grasshoppers. Adult Meloidae feed on pollen and can be frequently found on flowers, although E. rufodorsum also feed on green parts of vegetation. Both species were found in Lido’s ruderal habitats with white sweetclover, thistle and bugloss.

Orthoptera

Large areas of naked dirt are popular habitats for the blue-winged grasshopper (Oedipoda coerulecens) and the Italian locust (Calliptamus itallicus). In Slovakia these species are abundant in warm areas.

We also detected the occurrence of more interesting species, such as the Aiolopus thalasinus and Dociostaurus brevicollis grasshoppers, which are endangered in the Czech Republic to a certain extent (VU and CR), although both species are least concerned – LC, at the European level. Dociostaurus brevicollis lives in open biotopes with naked dirt which we can also find at the monitored site; the Aiolopus thalasinus grasshopper lives in salt marshes and flooded or wet meadows with naked soil. However, this is a mobile species and its imago can be observed far from their reproduction sites.

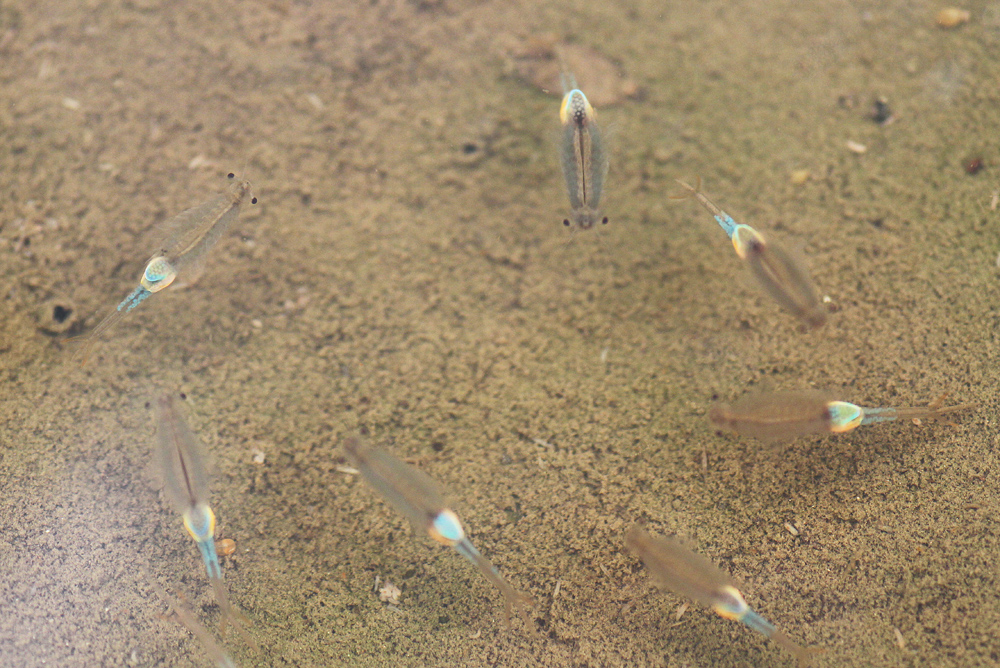

Notostraca

Puddles created on dirt roads after rain are the habitat for specialized fauna. Notostraca, which were represented at this site by the Branchipus schaefferi species, are its most distinctive representative. This is an ancient group of Crustaceans whose origin can be traced back to the Paleozoic Era. They are not able to survive in permanent water reservoirs because they would not be able to compete with predators; for this reason, they only inhabit puddles. After the puddle dries up the adult individuals die out, but their eggs survive. They are incredibly resilient; they can endure extremely high and low temperatures, and even survive passage through the digestive tract of birds, which is also why their appearance is quite widespread.

The fact that the puddle must have only a minimum of vegetation is essential for their survival. Otherwise, the water would evaporate too fast and they would not be able to complete their life cycle. That is why dirt roads with the infrequent traffic are crucial for preserving this disappearing microhabitat.

Conclusion and Recommendations for Management

The entomofauna of Lido is interesting from a conservation perspective and deserves our attention. I consider solitary trees surrounded by tall herbal vegetation with flowers accompanied by naked dirt and periodical puddles as the biologically most valuable. The area around the embankment is mowed once or twice a year which creates conditions for ordinary meadow species, and the adjacent alluvial forest provides shelter for a special albeit relatively poorer fauna of pollinators. The current mosaic of biotopes provides living space for precious, mostly thermophilic fauna.

Various early-succession areas with large portions of naked dirt are among the most underappreciated biotopes. The dry and warm microclimate of these places suits grasshoppers, bees, sphecidae and many others. The lifespan of such places is very short if left at the mercy of nature; they disappear and their fauna with them. It would be good to realize that pollinators are inhabitants of mostly open, deforested landscapes. Suitable fragments for the survival of these species are quickly disappearing. That is why the sites should be actively managed and new sites where, circumstances permitting, should be created.

The “organized” urban vegetation, pebble mulches and regularly mowed lawns may suit our tastes and desire for neatness, but these are biologically erased places. Society becomes wealthy, cities develop quickly and these little spots and “new wild” areas scattered around the cities are gradually swallowed up. The long-term decline of biodiversity in the city has yet to be monitored by anyone, but it is possible that one of the most important shelters of biological diversity will gradually be lost.

That is why, from the perspective of the preservation of the biological value of Nové Lido, its current character should be preserved as much as possible. I consider the management of mowing once a year by the end of vegetation season (September-October) for open grassy spots outside of the embankment as suitable; it should have a mosaic character in which 50% of the area is not mowed. Ideally, the areas with invasive species or fewer flowers should be mowed.

Dead, drying out or fallen trees should be left where they are. If necessary due to safety reasons, a tree should be taken down and left there. The targeted planting of replacement trees and the removal of invasive species, primarily Ailanthus, Japanese knotweed and goldenrod, is recommended. Furthermore, unreinforced surfaces, dirt roads in particular, should be kept free of vegetation. The alluvial forest should be left without any management interventions, however maintaining existing clearings and flowering edges by occasional mowing (once every one or two years) could be considered.

Translated to English by Elena & Paul McCullough

Mgr. Marek Semelbauer, PhD. Is a researcher at the Institute of Zoology of the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava. He studies faunistics, Diptera morphology and ecology and has spent many years working on various environmental topics, in particular, the conservation of non-forest biotopes.

Location Soví les

Aesculapian snake, Soví les

Large copper (Lycaena dispar), a common species of wet meadows protected by European legislation

Solitary clover bee melitta (Melitta leporina)

Anthidium spetemspinosum bee on vetch

A female wool carder bee (Anthidium florentinum) approaches a bugloss flower

The wool carder bee (Anthidium florentinum) guarding his territory

The solitaryNomiapis diversipes male has distinctive spurs on its hind legs

The cuckoo bee –Pasites maculatus lays its eggs in the nests of Nomiapis diversipes

The cuckoo Epeolus tarsalis, a rare and disappearing species

Female robber fly (Dasypogon diadema)

Female robber fly (Dasypogon diadema) catches western honey bee

Male robber fly (Dasypogon diadema)

Caliprobola speciosa on dead wood

Caliprobola speciosa

The Sphiximorpha subsessilis closely resembles a solitary wasp

The Sphiximorpha subsessilis males guard their territory on tree trunks

Brachyopa bicolor(Syrphidae), larvae develop in tree sap

The Micromitra stupida (Bombyliidae) has only recently been discovered in Slovakia

The Epicauta rufidorsum (Meloidae) on white sweetclover

The Mylabris variabilis (Meloidae) on thistle flower

GrasshopperAiolopus thalassinus

European locust (Dociostaurus brevicollis)

GrasshopperChorthippus parallelus, one of the most common grasshoppers

The Branchipus schaefferi resides in puddles