THE LIDO AFFAIR OR ABOUT THOSE FOR WHOM NATURE MEANS NOTHING

Mikuláš Huba

There’s an old chestnut which goes something like this: the best architect is the one is who takes such a strong stand that certain locations remain undeveloped. Since the time that this observation was made, the developed areas have dramatically expanded and the undeveloped areas have rapidly shrunk and today this observation would be twice as topical.

Yes, Lido was a popular place when I was young. But the Bratislava of my youth was no more than a third of what it is today; the developed area was several times smaller and there was more greenery within the city – in absolute and relative numbers.

And then architects and developers came from a completely different approach in comparison with the message of the aforementioned bon mot. According to today’s supporters of the urbanization of Lido and the nature between the Old Bridge and the Apollo Bridge, there is NOTHING there. This is how they define and reveal themselves, and present their vision of the world. They are the same as or similar to those for whom the area below Castle Hill, Park kultúry a oddychu and its surrounding greenery, Bratislava’s vineyards, Pečniansky Forest, the Iuventa premises on Búdková Street, the old gardens in Slávičie údolie, Koliba, the Karlova Ves cove of the Danube and other Danube branches near Bratislava or the Devínska Kobyla hillsides also meant NOTHING. And if we go further from Bratislava, we can talk about nature in national parks, for example the surroundings of the Štrbské and Vrbické pleso mountain lakes.

My vision of the world is the complete opposite.

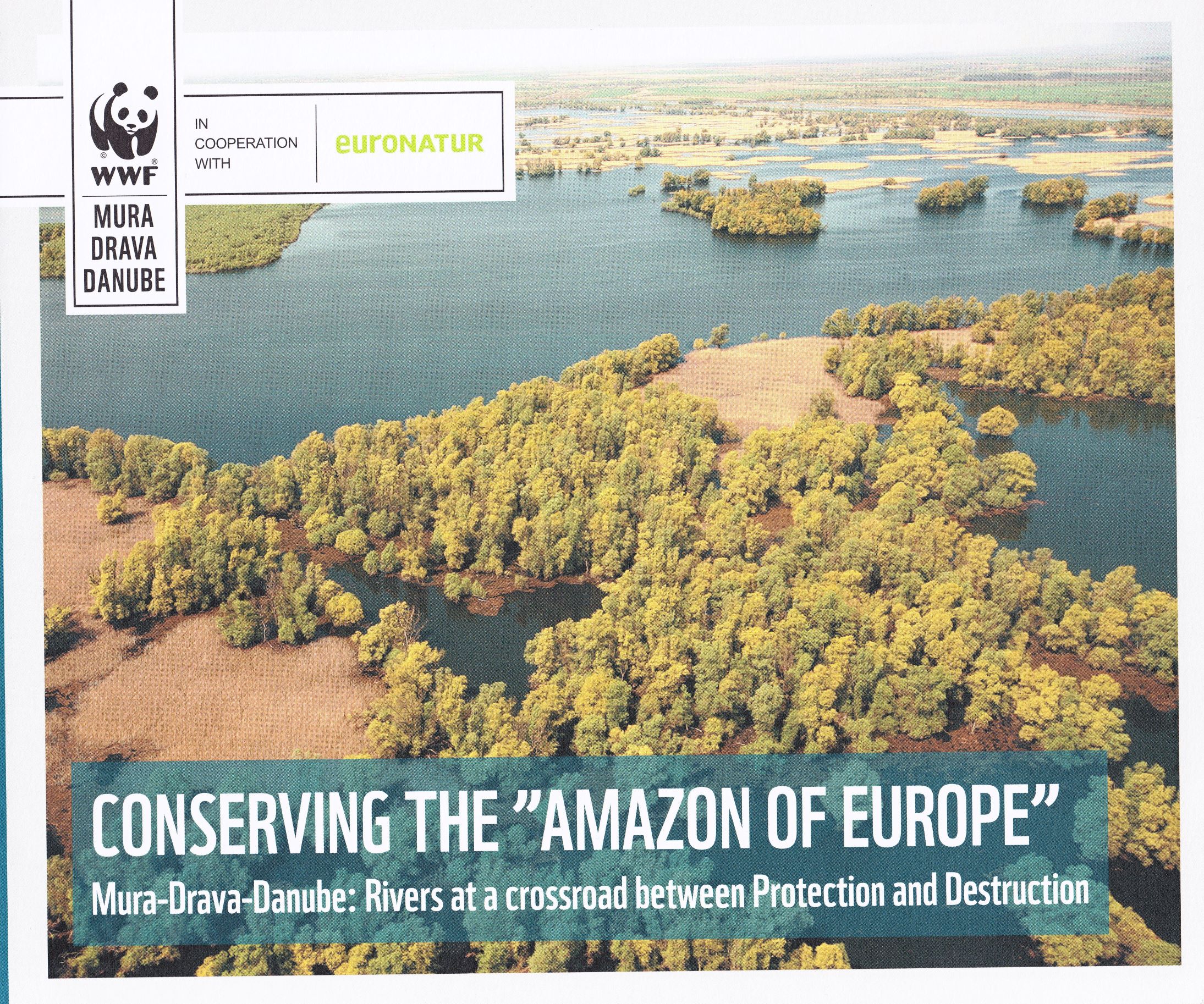

I can see the lush alluvial forest on the right side of Danube under the old bridge and the popular dock hidden there. The fact that this forest has been preserved is a minor miracle in my eyes and a blessing for this city, and something that other, smart and far-sighted people would protect like a hawk (also due to the growing climatic changes and their negative impacts). This massive greenery on the right bank of the Danube has great micro-climatic, ecological and aesthetic value and particularly psycho-hygienic value – since it creates a calming counterbalance to the surrounding urbanized environment.

But this zone of nature between two Bratislava bridges also has urban, supra-urban and even international value because it is part of the Danube bio corridor. Therefore, it is our duty to protect it not only for our own sake, but for the sake of the world. This is especially important considering the fact that we have already managed to destroy almost everything natural on the other side of the Danube in Bratislava, as a result of which, for all practical purposes, the direct connection of the Danube and Carpathian bio corridors between the Lafranconi Bridge and the Winter Port has ceased to exist. Now only the right bank remains, and if we destroy and denude it, we will bring an end to the functioning of the Danube bio corridor once and for all.

Yes, all sorts of things can be found in that forest surrounding the former Lido, including illegal garbage dumps. But instead of demonstrating that it is NOTHING, it only holds up a mirror to those who should be taking care of the city and who allow people to do whatever they want with the city’s precious nature. The garbage is a problem with a relatively easy solution. However, concrete, which some people would like to see there, would be a problem much harder to solve.

I am no stranger to nostalgia, but I understand that Lido will not return to its original place and it will be replaced by a city beach near the Old Bridge. I consider the developers’ activities, hidden behind the popular phenomenon of Lido, to be as sincere as the names of the parks (River Park, Green Park, etc.) gates or gardens, when these romantic names or euphemisms hide the most un-natural complexes made of glass and concrete.

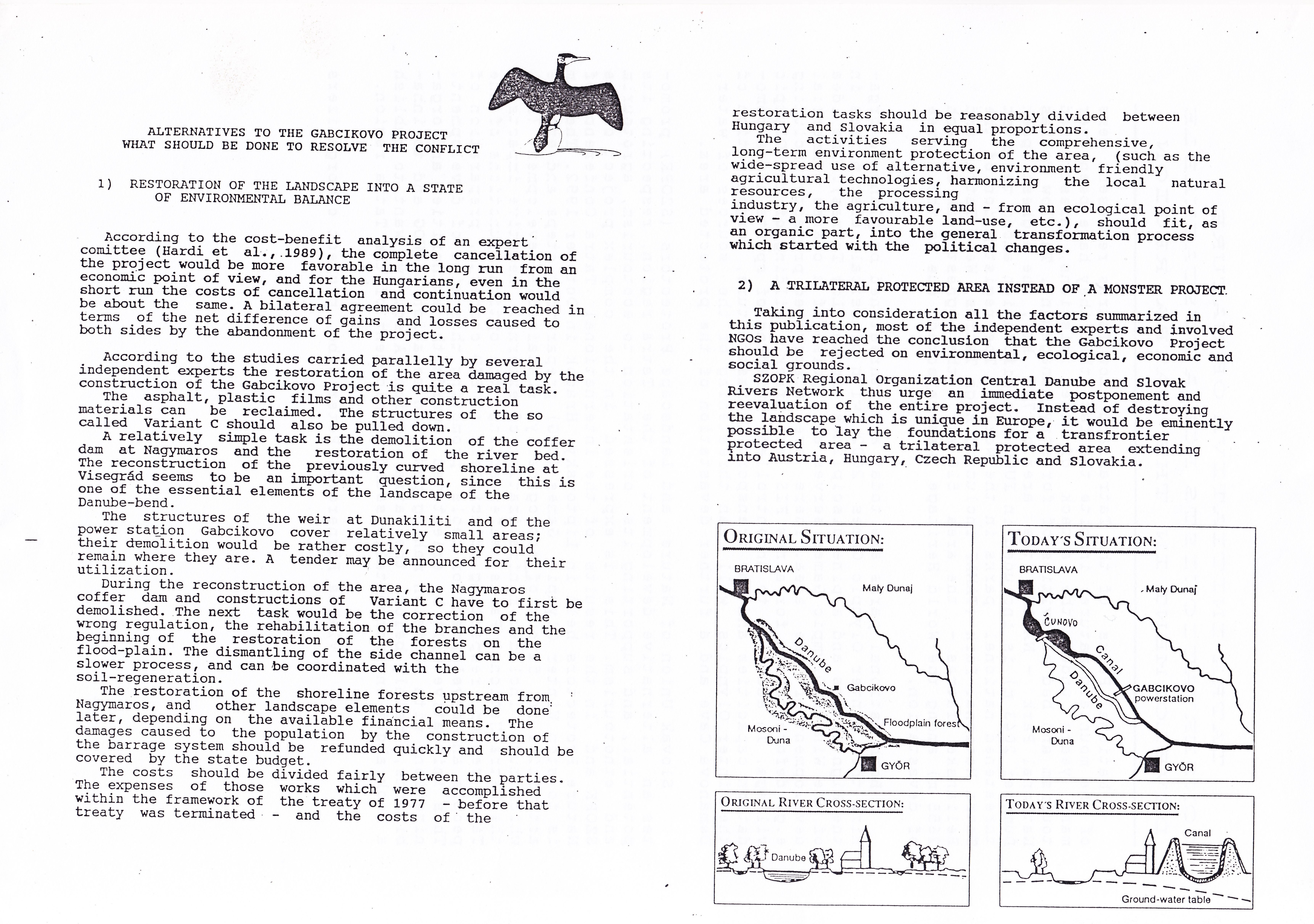

I would like to briefly revisit the libretto of this event, in which it is rightly stated that Bratislava’s environmentalists (not to mention, scientists, professional environmentalists, journalists and even clerks at the community level) were against the original Gabčíkovo-Nagymaros dam project in the 1980s, which would have also essentially changed the right bank of the Danube near Bratislava. However, at that time, since it was impossible to block this technical “grand project” which was already in progress, they at least requested a principal change, and were more or less successful; only the Gabčíkovo dam was implemented and in significantly modified form. I mention this because according to the original plan, all of the Danube’s alluvial forests near Bratislava were to be cut down and the level of the water in the reservoir (with effects reaching all the way to Bratislava) was to vary daily according to the so-called peak electricity production regime. If this had happened, this discussion would be pointless and the entire project would not be called New Lido, but for example Stinky Mud. In other words, we saved Bratislava’s alluvial forests out of our love of nature and people and not the profits of a few businessmen who have repeatedly convinced us of their lack of respect for our natural and cultural heritage and their fellow citizens.

We first summarized our idea of the future of the Danube’s nature in the Proposal for the Conservation of the Bratislava Alluvial Forests and later in the Proposal for the Declaration of the Danube Region National Park, which we submitted to the Slovak government in February 1987. This document was neither accepted nor rejected. It is still alive and it has been recently supported by almost all of the relevant stakeholders: the Bratislava self-governing region, the city of Bratislava, the relevant city boroughs, the Presidium of the Slovak Academy of Sciences, the Union of Towns and Cities of Slovakia and the Slovak Conservation Union.

Just to be clear. This is not about fencing in the alluvial forest between the Old Bridge and the Apollo Bridge, or declaring it a strict natural reserve. After all, it already contains a dense network of pathways and the aforementioned dock. Nobody is against sensitive and rational infrastructure improvements in the form of natural walkways, benches, waste bins and educational trails. Some of the areas, especially near the bridges, require revitalization or re-naturalization. I admit that that the area could be more welcoming to people, and thus add to the character of city. This is after all what modern concepts of national or natural parks are all about: protecting nature and providing people with appropriate access without disturbing the long-term functioning of natural eco systems.

Moreover, all of this is directly within the territory of the capital city, which is unique, but not unprecedented. After all, Donau Auen National Park begins within the city limits of Vienna and the enclave of the Duna – Ipoly National Park is part of Budapest. Nature along the rivers is protected in many large cities. Perhaps in every city in Europe in which some nature remains, but we can say without exaggeration that we are the only country in the region which does not protect the values of the Danube nature comprehensively and conceptually, and from time to time we even act as if these unique places have no value. Yes, as if they were NOTHING.

I am aware of the fact that what I have written here has nothing in common with the “development” ideas of the developers concerning this area. Quite right. It seems to me that they have already developed Bratislava excessively and mostly with unfortunate results. They could at least leave some space for their successors, who hopefully will be more welcoming and sensitive to nature, more environmentally aware, more sophisticated and in general less mercenary, unscrupulous and expansive.

Resumé: If the relevant zoning plan is to be altered, let it not be altered in favor of developers’ plans, the pouring of concrete and the abuse of attractive natural sites, but in a way that local nature can be declared intact, i.e., a non-built-up area and it can be extended under the bridges to ensure the functional continuum of the Danube bio corridor! This type of zoning plan has worked in nearby Brno for a long time.

Prof. RNDr. Mikuláš Huba, CSc., is a geographer, environmentalist, landscape ecologist and civic activist. He graduated from the Faculty of Natural Sciences of Comenius University and lectures at several universities. He is also a researcher at the Geographical Institute of the Slovak Academy of Sciences. He has been active in the conservation movement at home and abroad since 1975. He was the initiator of the international Danube Declaration and the head of the team of designers of the Danube Region National Park. He has actively participated in key international events related to saving the Earth and is the author of dozens of publications and regularly comments on social life in the media and on Facebook. He was twice elected head of the Environmental Committee of the Slovak Parliament.

PHOTO CREDITS: Archív Mikuláša Hubu & Michal Huba