ON THE

IMPOSSIBILITY OF DRAWING A RIVER

Maud Canisius, Myriel Milicevic

A border; a route of propagation; a contested line; an economic backbone; a source of energy; a multitude of habitats; a place of spirits and lore; a connection through time and cultures; a source of energy, water and life... a personhood. There are countless ways to look at a river, and yet so many remain invisible in today's cartographic depiction.

In reference to Umberto Eco’s “On the Impossibility of Drawing a Map of the Empire on a Scale of 1 to 1”, we took on the challenge to draw a map of the river Danube in the Lido area of Bratislava. The Lido area bears conflicting interests between urban developers and river communities, a typical situation in these terrains. How does the way different actors look at a place influence what is visually represented? How do legal constructions relate to visual representations of rivers? How can we differentiate between rights to the river and rights of the river?

Having spent four days with this small section of Europe’s second largest river, exploring with humans and through the eyes of nonhumans possible river relationships, we formulated a set of steps, or exercises, for analysing the impossibility of mapping the river.

1. Immerse yourself

2. Look beyond

3. Connect with river-land communities

4. Include the river

5. Start to draw

6. Don't stop

1. Immerse yourself

How to put yourself in relation to a river?

In maps, the initial observation is normally done through a distant, objective view. For the Lido area, like most other places around the world, this approach translates into a wide set of materials available: historical maps, hydrological maps, demographic maps and vegetation patterns, to just name a few. Such maps are created through satellite images and measurement devices and are ultimately presented as two-dimensional projections. In order to perceive the river in many dimensions, other tools and senses are needed. To bridge the distance between the observer and the observed, a possible first step would be to remove the gap and move from a distant, objective view, into an immediate, sensorial encounter. For the river this could mean going for a swim or taking a small boat and start paddling.

Our direct encounter with the Danube stream took the form of a paddling tour. The first sensorial impression that we experienced upon entering the kayak and facing the vast river surface, was a feeling of helpless disproportion. It felt as though one could easily end up swept off to one of the countries downstream. Our senses registered the pressure of the wind, smells, balance, humidity, temperature changes and sounds. An awkward feeling of being exposed makes way for a comforting joy of being “away” and being carried. While respectfully paddling a short stretch upstream along the Lido shore, invisible currents made us almost drift off and stream-patterns around the bridge’s pillars taught us how the water finds its way around the huge impact of man-made structures.

Immersing into the place that should be mapped, reveals other characteristics and relations to the observer. Here, we were confronted with hidden currents, sensations and forces. These elements form a fascinating starting point for a map of the river.

2. Look beyond

What are the boundaries of a river?

Being on the water, being with the subject, forms the first step of a river relation. However, what is beyond the banks reveals a great deal about the river itself. Between the headwaters and the estuary the river transforms, transports and feeds landscapes. With its constant flow and changing patterns, the river plays important roles in hydrological and ecological networks.

On a walk with hydrogeologist Anna Kidova, she pointed out to us how the Danube is mostly channelled between man-made walls of boulders. This prevents floods, which may be beneficial for the humans living there, but at the same time keeps the fluvial forest from actually being fluvial. She continued to explain that in other places, the Danube has more space to accumulate sand and rocks, create meanderings in the landscape and therefore accommodate habitats for a diverse biota. There, the soft and somehow boundless boundaries characterise its shapes. In this state of being ‘walled’ in, the river speeds up and scrapes away its own gravel bed. With climates changing and irregular rain patterns increasing, the prediction is that water flows over and beyond the constructed walls. The river has shaped the land in the past, left its marks, and will continue to shape the environment in the future.

Being in the river environment made us aware of the different time-scales and how a stream reaches beyond its shores and beyond the blue line as it is typically represented on maps. The past is as important as the potential future it holds with its interplay of forces.

3. Connect with river-land communities

How to take the perspective of a nonhuman?

Corresponding to what Eco postulated, a map doesn’t include only geography, but also its inhabitants. But how to include their perspective of the river, if one doesn’t know who lives there and how they inhabit the space?

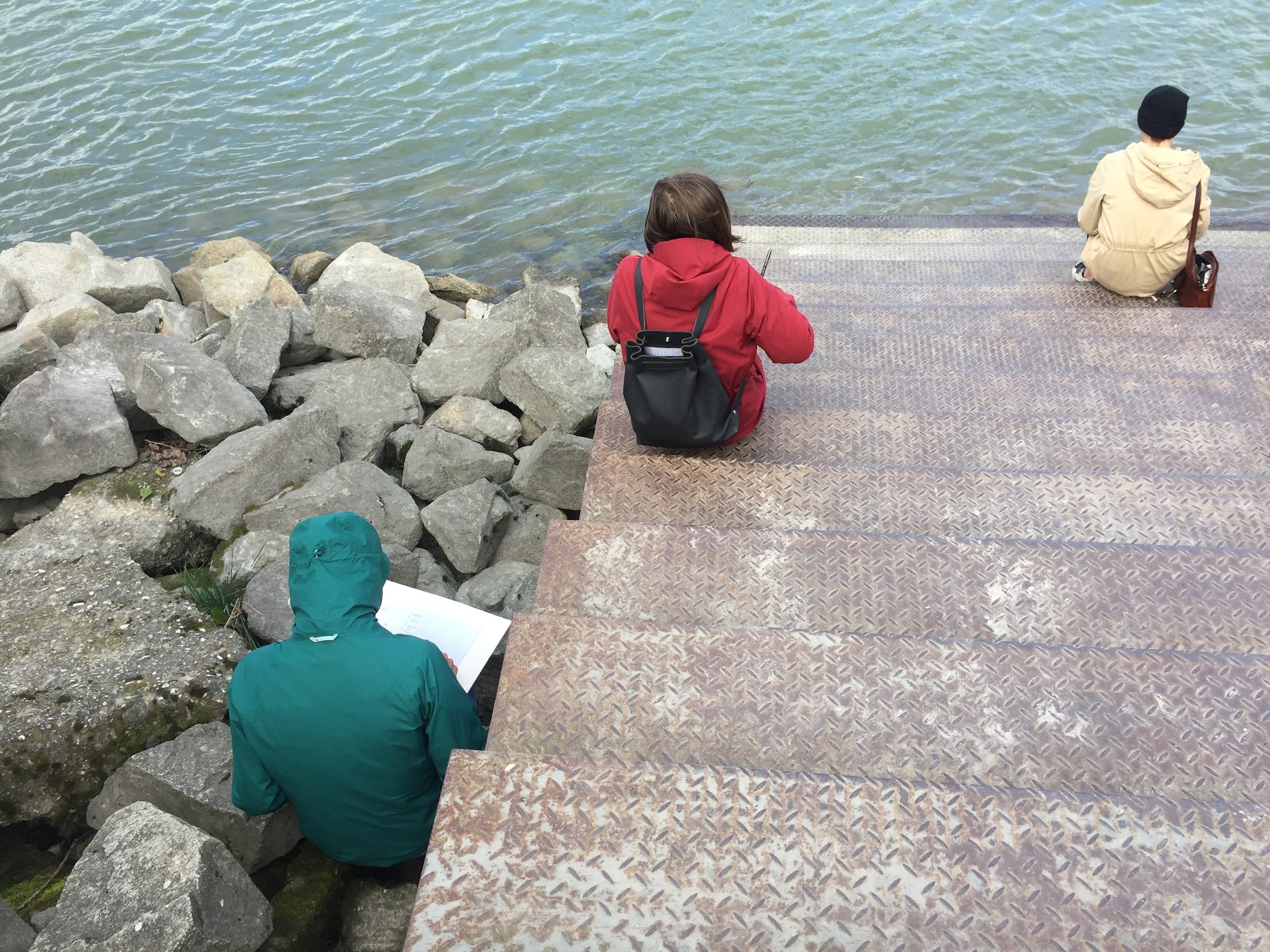

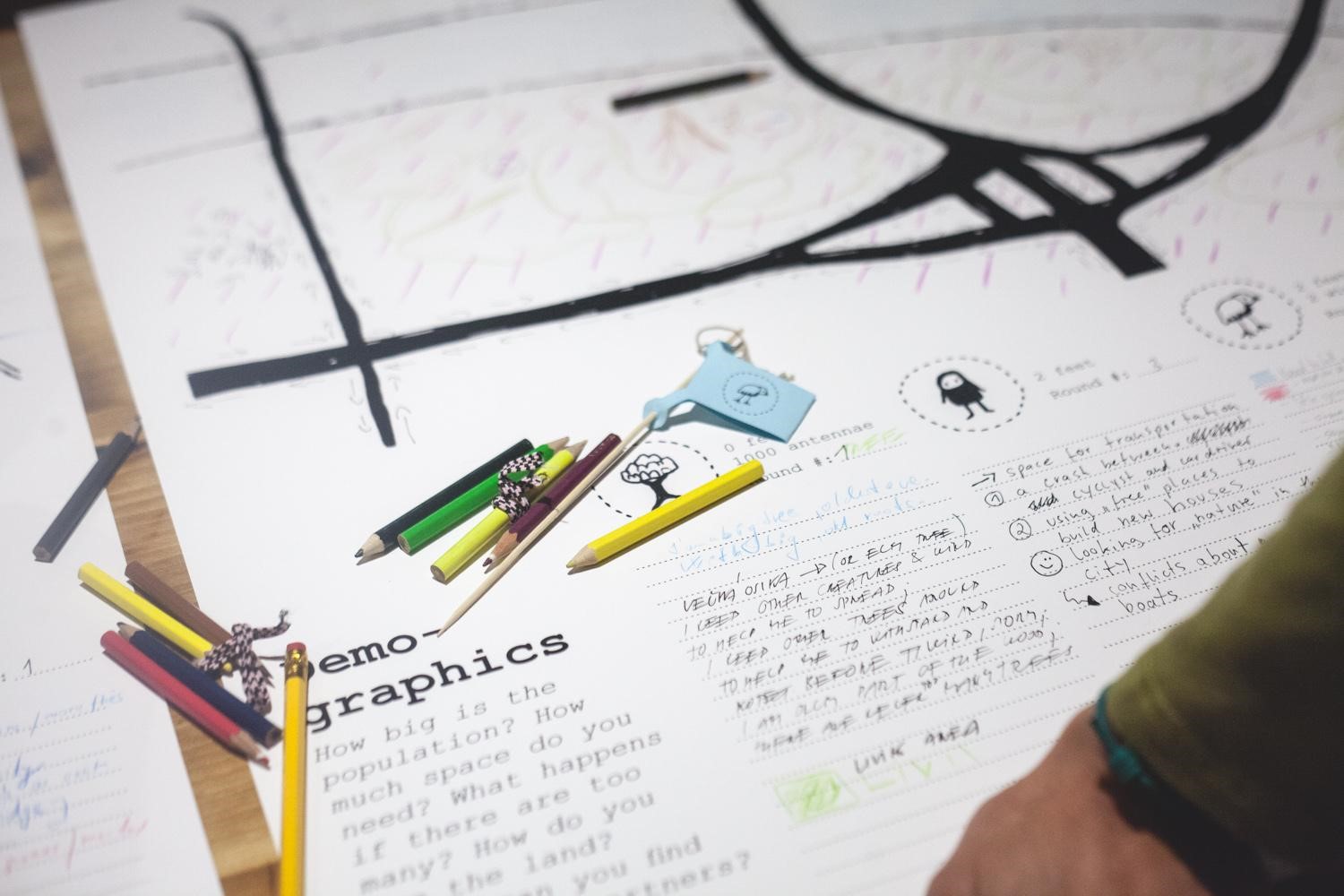

Therefore, together with the workshop participants, we first tried to find out and imagine who and what could be regarded as ‘inhabitants’. How would bugs, birds, fungi, shrubs, rodents, amphibians and many other living beings, including humans, chart their own environment? In the workshop, we tried to imagine who lives in the Lido area by using six groups as starting points: ‘0 feet & 1000 antennas’, ‘2 feet’, ‘2 feet, 2 wings’, ‘4 feet’ and ‘6+ feet’. Potential inhabitants that were a fox, birds, the old lady from across the river, spiders, and trees. In the second part of the workshop we went outside and trained ourselves in taking these perspectives with their different connections to this river environment. A difficult exercise, because each actor has a different dimension of scale, a different relation to time, a different colour scheme in which it sees, other signals it receives, other conflicts it fears, other forms of cohabitation and symbioses it enters, other needs of resources and paths it moves on. If there is one thing that connecting with the river communities taught us, it is that thinking with others is extremely hard.

What does this mean for drawing the map? In fact, it became quite an impossible situation at this stage already. Yet, through knowledge, observation, imagination and empathy, the human can lend a drawing hand to the nonhuman.

4. Include the river

What do we see when we see a river as a person?

While in Western society, rivers in general are respected for their economic, cultural and ecological services they provide to people, other, often indigenous cultures, have developed different relations with their rivers. To the Māori, the Whanganui River is a living ancestor, a person. For them the river is an indivisible and living whole from the mountains to the sea, incorporating all of its physical and metaphysical elements.1 In 2017, after 140 years of dispute, the Whanganui River was officially recognised as a legal person in New Zealand.

In Europe we don’t know of such an understanding of kinship with a river, but there are ways in which the Europeans see their rivers as persons. In different languages, for example, rivers are given a gender. While making its way through Austria, the Danube is regarded as female, however changing the gender to male once it crosses the border to Slovakia. From his or her source to the Black Sea, the Danube passes through ten different countries – more than any other river in the world. What would it mean to regard the river Danube as a transnational legal person? Would it make people along the Danube appreciate the river in another, a more personal way?

By acknowledging the river as an indivisible and living whole, the river should ideally be projected as a complete subject and not as partial cartographic pieces. As a subject in its own right, the question arises above all: how would the river draw or represent itself?

In reference to Narcissus, the son of the river god Cephissus and the nymph Liriope, who fell in love with his own reflection in the water (not realising it was himself and dying in vain), we held a mirroring cardboard in the air. The reflective surface allowed the river for once to see itself.

5. Start Drawing

In this step, we return to the epistemological precondition of a map. Because rules exist about how maps are systematised, and are based on categories that are represented in a legend, also our map needs an underlying system of criteria. Besides the standard view of the visual separation of water and land, non-standardised elements that are normally excluded from a map should be represented as well.

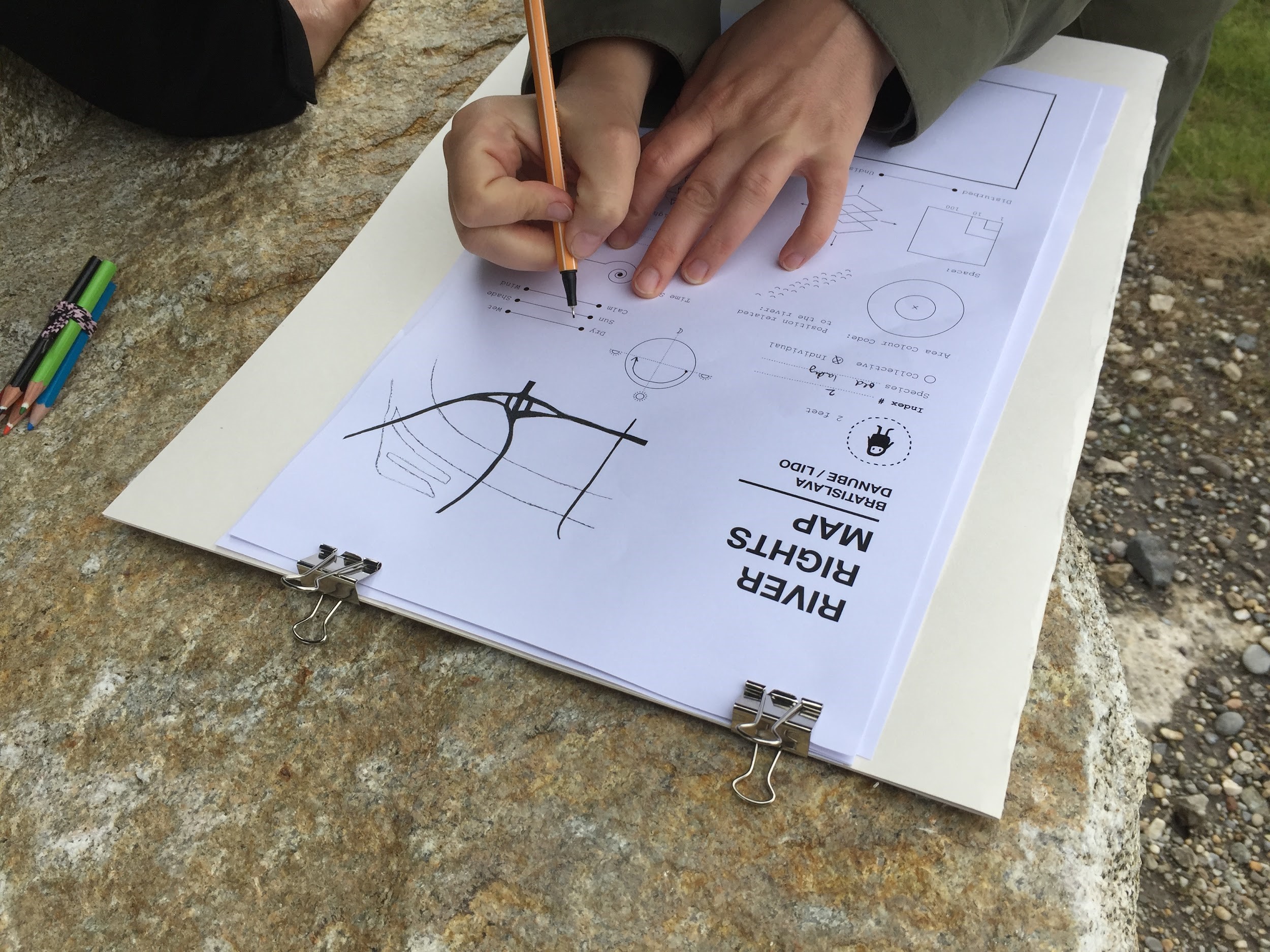

After going through the process of establishing relations with the river and its inhabitants, the uncountable elements that could be represented in this map were overwhelming. Trying to connect these elements and putting them in relation in a variety of ways, a range of possibilities for a legend emerged. Having set up our cartography studio on the river’s banks, we started not only representing the visible surface, but also the shadows in the water, the driftwood, the beaten paths, the forest density, the underground water currents, the pipelines, the different gradations of humus, wind patterns, telecommunication lines, chemicals, bird movements, position of various creatures over time, wishes for restricted areas for humans, ourselves as the cartographers within the map and also things that were outside the map.

Being in the place, we were constantly met with new requirements for the map. People walked by collecting trash, stories were told about old bunkers hidden underground, the sun’s movement changing the shadow play and insects we didn’t know the names of kept walking over the mapping paper. Drawing, mapping, criteria building became an ongoing process.

6. Don’t stop

One could say that we succeeded very well with the impossible attempt to draw a map of the Danube river in the Lido area: we did not nearly finish one of the above mentioned steps, the list of categories was in itself not even finished. With more time, with more knowledge, and more connections of what should be drawn in the map could be endlessly extended with uncountable things. What about all the myths and tales? What about the collective memory? What about the future?

Although we had a different objective than Eco with his map of the Empire, we come to the same conclusions. A 1 to 1 map always reproduces the territory unfaithfully. There are things left out of the map for the sake of systemisation, and because of a lack of knowledge, a lack of understanding or a lack of motivation. Furthermore, as soon as the 1 to 1 map is realised, the map is already not a relevant representation anymore. Although we do not and cannot know enough about a river to faithfully represent it, such impossible and unfinished maps can tell the stories of the relations that such an environment is made of. Just like the environments are always changing, so is the way they are represented and their stories are told. Attempting to take other perspectives, to invite others to the process and to include various worlds in a representation of a place hopefully in some way supports the debates around human-environmental relations and interactions. The lesson taken from this is: continue drawing.

On the Impossibility of Drawing a River was co-organized by Goethe-Institut Bratislava.

On the Impossibility of Representing a River

These reflections were extended and discussed in form of a performative conversation, together with anthropologist and photographer Thiago da Costa Oliveira and with jurist and socio-legal scholar Xenia Chiaramonte, and the river Danube itself in a “live stream”.

This conversation was facilitated by the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) in Berlin and part of the Anthropocene Curriculum event The Shape of a Practice.

https://shape.anthropocene-curriculum.org/events/on-the-impossibility-of-representing-a-river

PHOTO CREDITS: Maud Canisius