What Can Avifauna Reveal about Lido’s

Socio-Ecological Potential?

Soňa Nuhlíčková

Introduction

Birds have been a part of man’s environment throughout history. They announce their presence by their colours, flight, and song, which all represent an inseparable aspect of the harmonious environment of humans. The harmony of nature and the singing of birds frequently represents the only oasis of relaxation amidst the stressful pace of the city. Therefore, it is no accident that birds are considered to be valuable bio-indicators of a healthy environment where people simply feel good.

For birds, life in cities essentially differs from their natural environment. Cities provide new possibilities, such as easily accessible food, new places for the building of nests, and safe hideaways from predators. However, coexistence with human beings does not bring advantages alone. In comparison to their natural environment, birds have had to adapt to changes, such as noise from infrastructure, the omnipresence of human activities, new predators, and a permanently shrinking natural environment. As a result of these essential changes, some species have disappeared altogether from the urbanized environment, while others have successfully adapted.

The aim of this research was to identify which bird species live in the centre of Bratislava’s urbanized environment; in particular to record the number of bird species in selected areas. It has resulted in ornithological data which may contribute to identifying the most significant spots from the perspective of Lido’s socio-ecological potential.

Methodology

The research of avian communities was carried out during the 2021 breeding season - from late March to the first half of June. The territory was visited in aprroximately monthly intervals (March-Jun) with the aim of capturing the nesting of early species and late migrants.

The point transect method, according to which the observer records all seen and heard birds detected from 50 or 100 meters from a point for five minutes, was used. Because birds have wings and are extremely mobile, individual recording points must be at least 300 meters from each other. In accordance with this method, nine points were selected to cover the entire territory of Lido (see Fig. 1).

Individual bird species were identified by using standard identifying keys, such as those of Swensson et al. (2009). The methodology for establishing the bird species and their numbers was designed according to Janda & Řepa (1986), Kropil (1992), and SOS/BirdLife Slovensko (2013).

Results

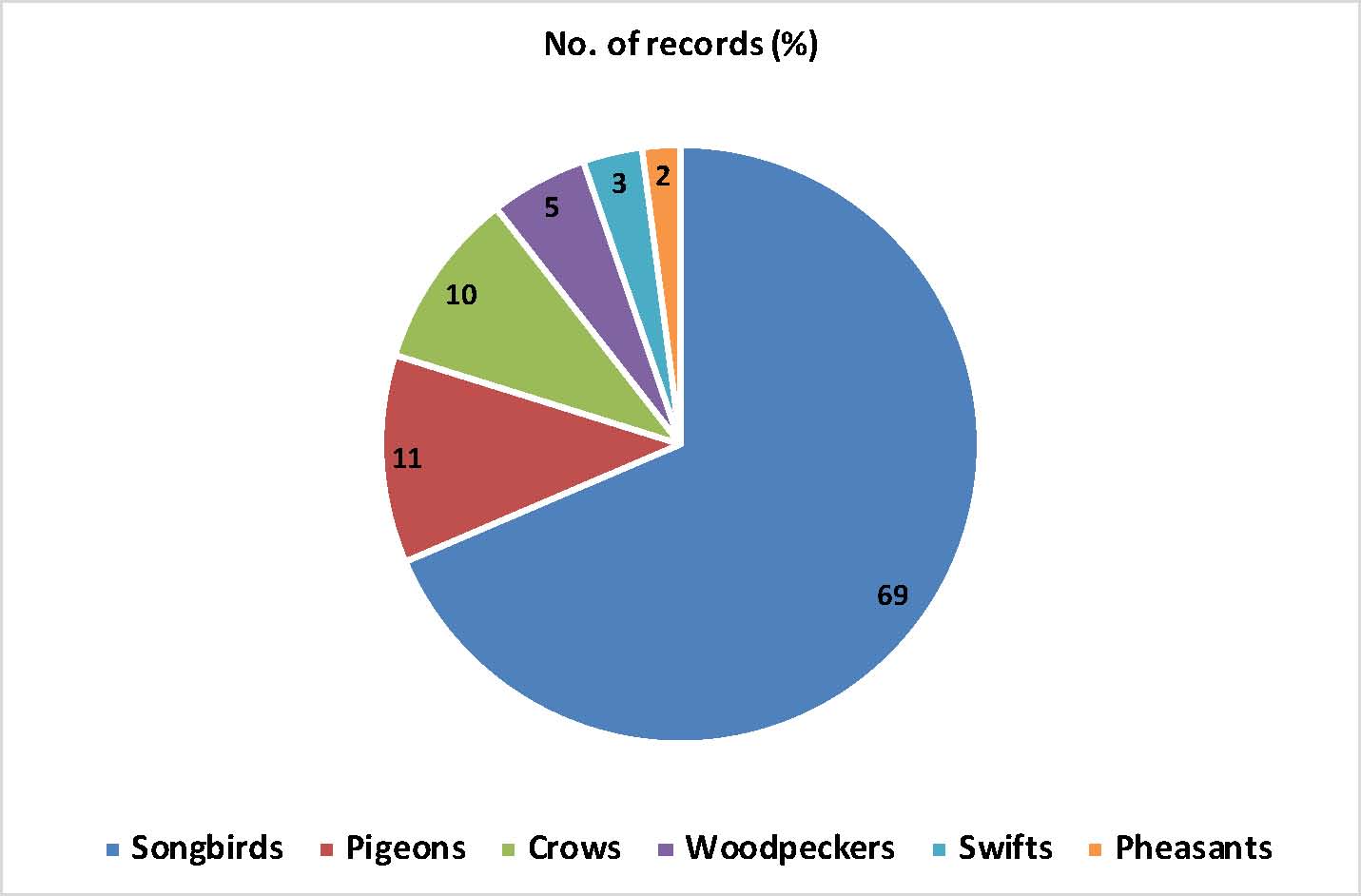

A total of 45 bird species were identified. The results showed that the Lido territory provides suitable conditions for the four largest groups of birds: small songbirds (69%), pigeons (11%), crow family birds - Corvidae (10%), and woodpeckers (5%) (see Graph 1). The most frequently recorded songbird species were the Common Starling (Fig. 2), the Great Tit (Fig. 3), and the Common Chaffinch (Fig. 4). Some of Lido’s smallest inhabitants included also the Eurasian Wren (Fig. 5) and the Long-Tailed Tit (Fig. 6), which we can see when wandering through an alluvial forest.

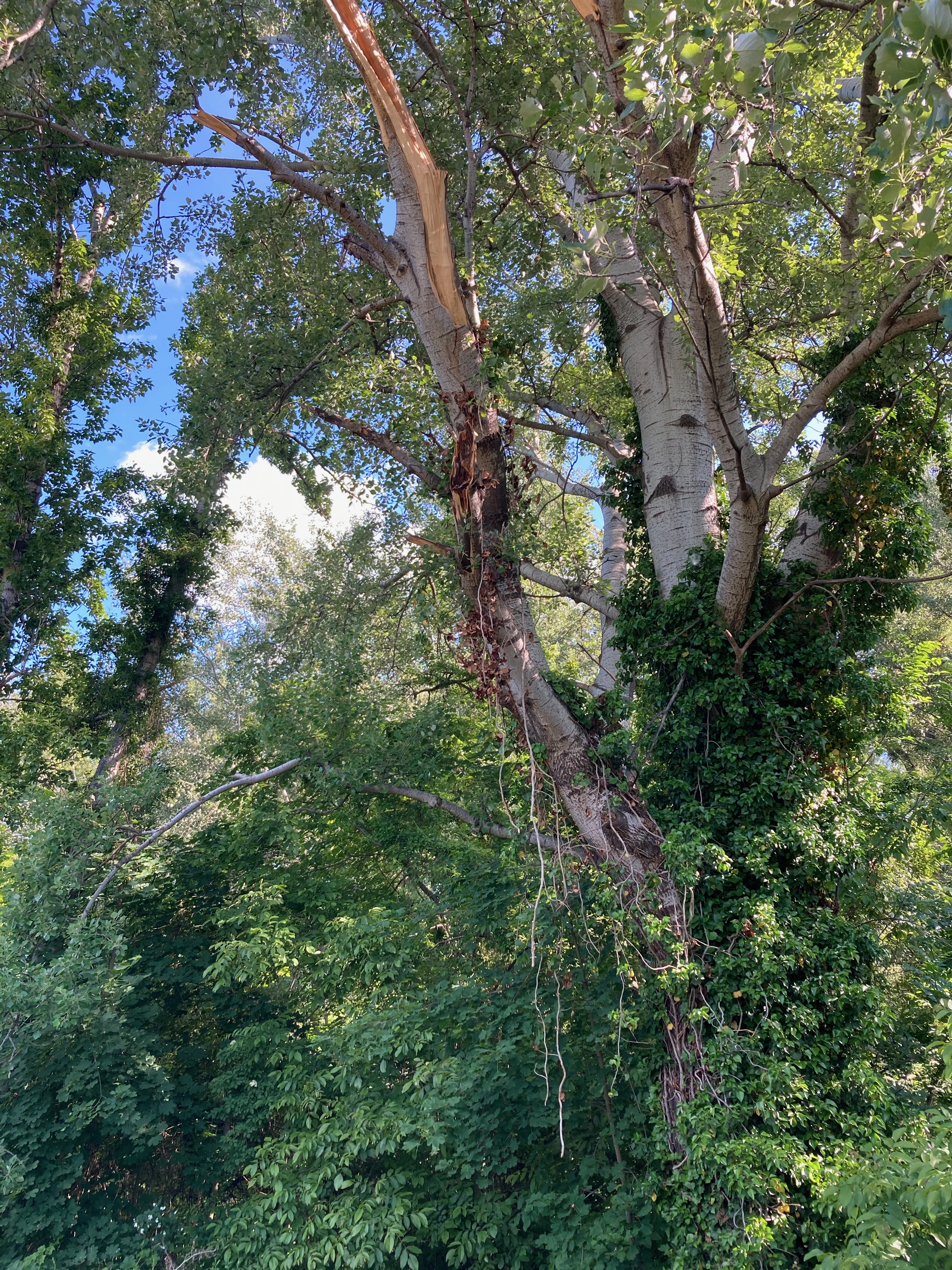

From among pigeons, the Common Wood Pigeon (Fig. 7), which has recently expanded successfully into urban environments, was the most numerous. Crows and magpies from the Corvidae species, which comprise the third most frequently recorded group, are extremely adaptable and are able to keep up with the changing urban environment. Another common forest species were the woodpeckers (Fig. 8 and 9). The key habitat of their occurence included especially the alluvial forests on the south bank of the Danube (Fig. 10) and old solitary trees (Fig. 11). They play an essencial role for other forest inhabitans which cannot make holes; however, thanks to woodpeckers, they can now move into forests (see Fig. 2).

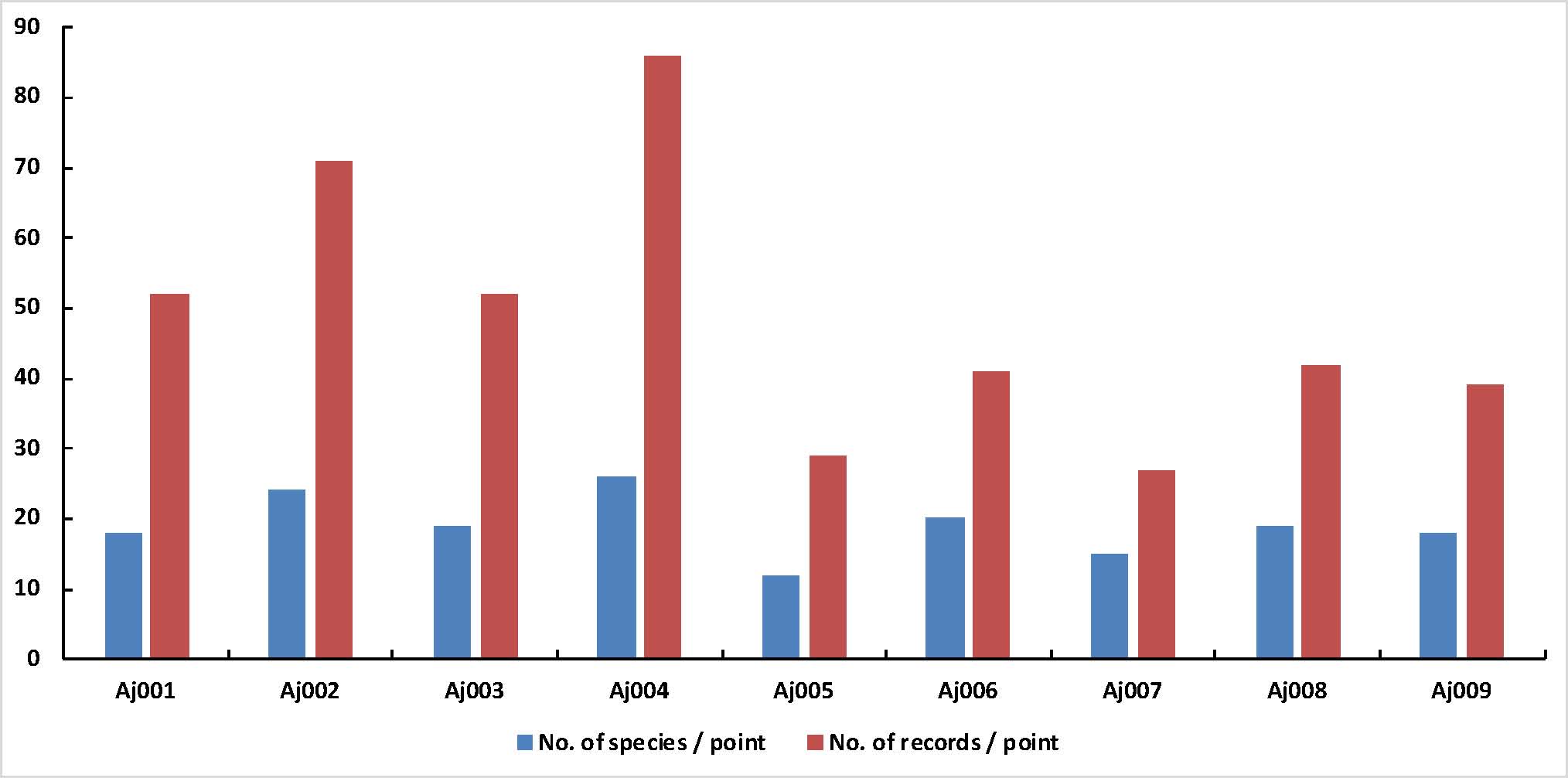

Along with gardens, old solitary trees have become the most significant places for avifauna biodiversity (see Point 4, Fig. 1). This is supported by the highest number of recordings of individual species (see Point 4, Graph 2). Nesting holes of starlings and woodpeckers have been found in old trees (Fig. 11). The Syrian Woodpecker, which deserves the attribute of synanthropic because it is not afraid of human presence, was also heard in the vicinity (Fig. 8). The European Green Woodpecker is a member of the green pecker family that feeds on ants (Fig. 9).

Certain species have managed to settle into extreme environments that have very little in common with nature and are the exclusive creation of man. Such environments include noisy bridges, where we can observe the Black Redstart, which is also known as the redstart (Fig. 12), and city pigeons. Areas with scant vegetation and the greatest degree of infrastructure influence (see Point 5, Fig. 1 and 13) have now become places for birds of the smallest significance. Older trees constitute an important component for the bird environment since they provide hiding and nesting places or food offer. Their absence also reduces the occurence of birds. Traffic noise affects not only birds, but also the ability of observers to detect them.

The aforementioned results show that the avifauna of the Lido territory copies three most important habitats: 1) floodplain forests vegetation along the Danube River 2) old solitary trees and gardens and 3) open areas with accompanying vegetation (for example, a soccer field). Floodplain forests along the Danube River (see Fig. 1; Points 1, 3, 6-9 and Fig. 10 and 14) along with old solitary trees (Fig. 1; Point 4 and Fig. 11) are the most important components of the Lido environment because they provide nesting and food opportunities for the majority of birds detected (e.g., sparrows, tits), as well as the more demanding species which need old trees for nesting (e.g., woodpeckers, starlings). For this reason, I recommend preserving the entire continuum of floodplain forests along the Danube River, as well as the old solitary trees that are found in the area. This should ensure several crucial functions for the central section of Bratislava. In particular, this refers to i) favourable micro-climate conditions in the city centre, ii) ensuring the successful reproduction of the biota, including birds iii) and eventually their successful migration among other islands of vegetation in the sea of urbanized land. This is why these types of biotopes may become essential from the perspective of a healthy environment for birds and the people who live in Lido.

Literature

Janda, J. & Řepa, P. (1986): Metody kvantitativního výzkumu v ornitologii. SZN, Praha, 157 p.

Kropil, R. (1992): Odporúčané skratky a symboly pre terénne záznamy pri kvantitatívnych výskumoch vtákov. Tichodroma 4: 21−34.

SOS/BirdLife Slovensko (2013): Metodika systematického dlhodobého monitoringu výberových druhov vtákov v CHVÚ. ŠOP SR, Banská Bystrica, 179 pp.

Swensson, L., Mullarney, K. & Zetterström, D. (2009): Collins Bird Guide. Second Edition, Harper Collins Publishers, London, 448 p.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank transit.sk and the Department of Architecture of the Institute of History of the Slovak Academy of Sciences for their financial support and cooperation. The testing and pilot application of the private database for biodiversity data collection was created thanks to Power Apps mobilné aplikácie. I would also like to thank Ján Svetlík for providing photographic material.

Mgr. Soňa Nuhlíčková, PhD.

A research assistant at the Faculty of Natural Sciences of Comenius University in Bratislava, Mgr. Soňa Nuhlíčková, PhD. studied the animal ecology on examples of birds and grasshoppers. In the present, she focuses her attention especially on bioacoustic identification of bird and orthopteran species. She is also involved in various environmental and conservation initiatives, including the conservation of the critically endangered, endemic bush-cricket in Slovakia.

For more details, see also ORCID account.

Graph 1. Proportion of recorded bird species (%) that have been included in the six identified groups.

Graph 2. The number of bird species and their records found at sampling points.

Fig. 1. Location of nine sampling points within the Lido territory.

Fig. 2. The Common Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) is a secondary cavity nesting bird. It means that this bird cannot make a hole on its own and depends on natural holes or holes created by woodpeckers.

Fig. 3. Great Tit (Parus major).

Fig. 4. Common Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs).

Fig. 5. Eurasian Wren (Troglodytes troglodytes) – one of the smallest bird inhabitants in the urban environment of Lido.

Fig. 6. Long-Tailed Tit (Aegithalos caudatus) - as the name suggests, this species is characterised by a strikingly long tail.

Fig. 7. Common Wood Pigeon (Columba palumbus) - belongs to the large species of pigeons, which has recently settled successfully in urban conditions.

Fig. 8. The Syrian Woodpecker (Dendrocopos syriacus) is one of the species that frequently occurs near people.

Fig. 9. European Green Woodpecker (Picus viridis) - this is a striking, green species of woodpecker that specialises in consuming ants.

Fig. 10. Old poplar trees are of crucial significance in terms of breeding of many bird species. The nesting tree of a great spotted woodpecker (Dendrocopos major) can be seen here.

Fig. 11. Old groups of trees became the focal point for the nesting for several cavity breeding bird species, such as woodpeckers, starlings, and small songbirds.

Fig. 12. Black Redstart (Phoenicurus ochruros).

Fig. 13. The concrete environment of the nearby road infrastructure is the least attractive element for birds.

Fig. 14. Along with old trees, the floodplain forest on the river banks of Danube are the most important areas for birds.