Lido

– Geobotanic Characteristics of the Territory and Annotated Map

J.A.Šturma,

September 2020

Context

The area which is known as former Lido is a small part of the extensive Danube meadow system extending for dozens of kilometers upstream and downstream. Although the present state of the territory does not closely resemble a natural riverside system, we can find a rudimentary version in the most ruderal sections. Alluvial forests have distinctive dynamics and geologically speaking, the present state of this territory represents only a temporary period. Thus, the Lido forest communities can undoubtedly be considered to be a continuation of an ancient alluvial ecosystem, which at the moment is severely damaged.

character, structure and distinctive features of the territory

Lido is a mosaic of the succession of anthropogenic and “natural” biotopes starting from bare concrete up to the old-growth shade alluvial forest. Construction activities have enriched the local landscape by biotopes which would not naturally occur here - "spaces" under bridges, backfills and a diverse mixture of wooden plants in allotment gardens.

general recommendations and strategy of the case for former Lido

• revitalization of riverbanks and renovation of hydrological regime

Lido’s current hydrological situation is sad in comparison with its historical status. The Danube’s side branches were filled in; pools no longer exist; and the natural riverside vegetation was destroyed due to the artificial regulation of the banks. The only option (although probably not realistic) is the revitalization of the riverbanks and the restoration of pools and at least a section of the filled-in branch. However, we are moving towards a gradual shift of the present communities towards drier types - oak-hornbeam forests and subxerophilic grasses.

• intervention-free regime in alluvial forests

The alluvial forest is represented by several types of growth - from the “old-growth” sections up to the heavily visited park nature. However, maintaining segmented forest floors and retaining dead wood, including tree trunk torsos which serve as dens, are essential. This in fact is an intervention-free regime; increased park landscaping in an alluvial forest is absolutely the wrong approach.

• care for solitary wooded plants and old cultural riverside landscape

Aside from species diversity, Lido also has an extremely rugged landscape. This ruggedness has many levels and layers, including the incidence of solitary wooded plants, which reflects the oldest preserved history of this territory and in several places, it most probably represents a relic of the “ancient” cultural riverbank landscape, in particular, massive specimens of Quercus robur, Populus alba andFraxinus excelsior. This layer is essential for Lido’s biological value and genius loci and it should be actively cared for (for example by replacing dead trees).

• ephemeral biotopes

Temporary, ephemeral biotopes represent an essential part of the biodiversity of the territory; however, their protection or conservation is difficult to grasp and frequently difficult to implement. Therefore, in general it is necessary to avoid additional sowing and artificial “greening” and to leave certain sections of Lido accessible to mechanical disturbance, such as cyclocross playgrounds and various small areas that cannot be specified.

• transformation of extinct allotment gardens

The bizarre landscape created by abandoning the allotment gardens is ideal “material” for the creation of unusual forms of extensive parks. The garden cultures, fruit trees and structure of the plots are mixed with an expanding riverbank system and creates a unique biological and landscape mixture. It is essential to avoid the destruction and bulldozing of such territories and instead to provide sensitive “punk” interventions and thus make the entire structure gradually accessible.

• what to do with invasive species?

The entire Lido territory is significantly affected by plant invasions. In addition to common invasive species, less obvious examples are also found (for example Celtis occidentalis); it is estimated that one third of the local flora consists of neophytes and they cover more than half of the entire vegetation cover. However, intervening against invasive species is not recommended as due to the character of this territory (near the river, main roads, extensive allotment gardens) the invasive species will most probably never disappear.

Instead, the handling of invasive species should consist of the proper biological management of biotopes in which certain invasive species are not desirable. This pertains to the mowing of cultural lawns, the regular mechanical disturbing of subxerophile biotopes and the restoration of a hydrological regime of drying alluvial biotopes.

![]()

Massive specimen of Populus nigra, massive growth of Clematis vitalba - "old-growth forest interior" of polygon No. 43

![]()

High brownfield in unused running polygon – dominated by Artemisisa vulgaris. Polygon No. 51.

![]()

Grapevine -Vitis vinifera – one of four dominant species of creepers in deserted allotment gardens. Polygon 32.

![]()

Oak-hornbeam fragment in polygon 13.

![]()

One of few semi-natural sections of the Danube riverside created by the erosion of artificial regulations. Polygon 44.

![]()

Parietaria officinalis, Mediterranean species of nitrophile locations, extensive wild growth.

![]()

Chenopodium botrys, rarer plant of early succession in polygon No. 1.

![]()

Occasional pools with subhalophile banks, polygon No.1. Obviously, this biotope is used by water birds.

![]()

Sporadic vegetation under the bridges is a new and very specific biotope, vegetation cannot grow in the driest and most shaded sections.

![]()

Kochia laniflora in polygon 1 – most precious plant species in Lido.

![]()

Small pool with fragments of marsh vegetation in polygon No. 49.

![]()

Pothead pool in alluvial forest, polygon No. 26.

![]()

Southern edge of the pile in polygon No. 11, covered by thermophilic plants.

![]()

Interior of the Janko Král Garden – an example of how not to landscape the Lido territory.

![]()

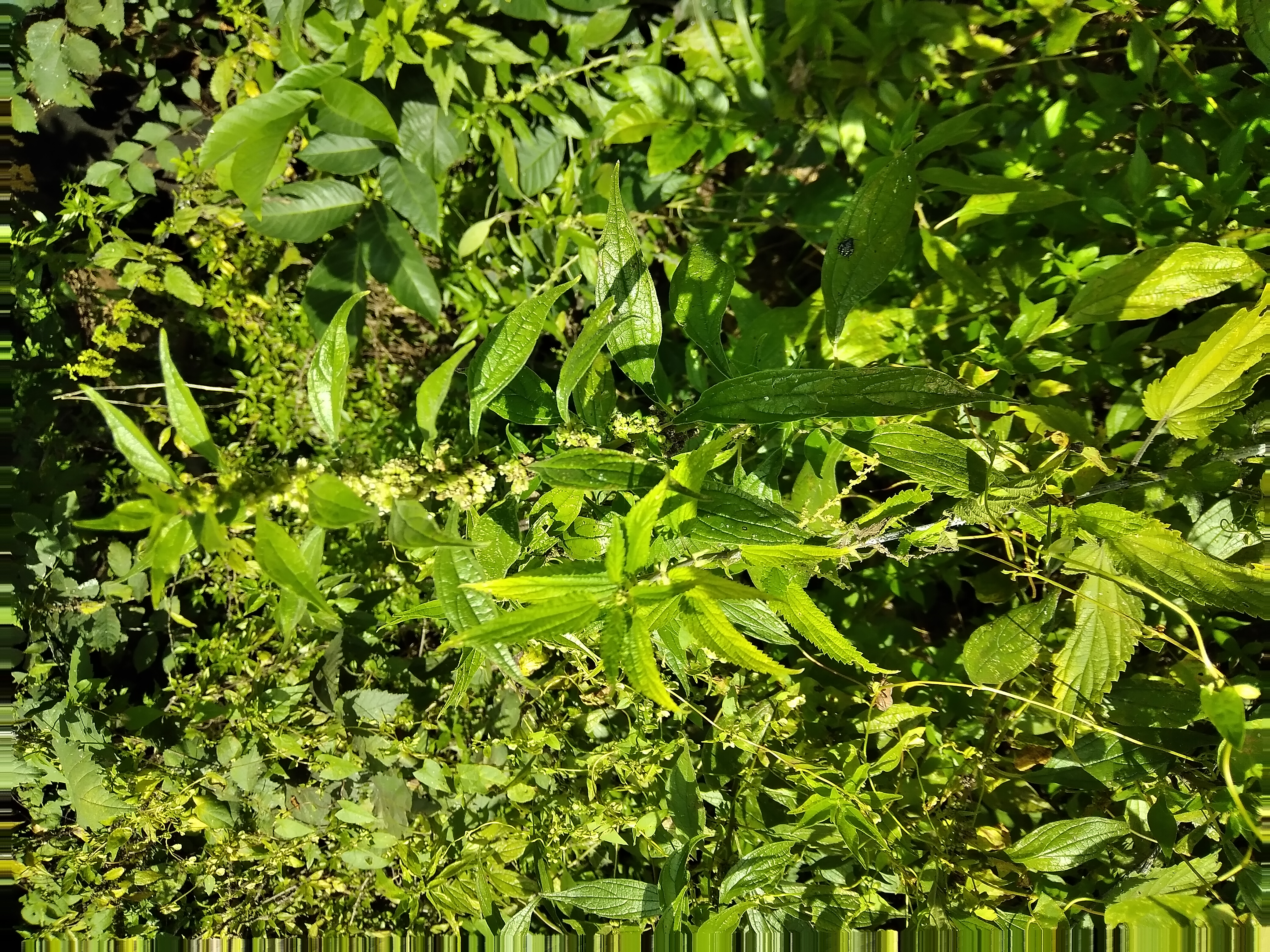

Helianthus tuberosus on the edge of the allotment gardens – common invasive plant here.

The area which is known as former Lido is a small part of the extensive Danube meadow system extending for dozens of kilometers upstream and downstream. Although the present state of the territory does not closely resemble a natural riverside system, we can find a rudimentary version in the most ruderal sections. Alluvial forests have distinctive dynamics and geologically speaking, the present state of this territory represents only a temporary period. Thus, the Lido forest communities can undoubtedly be considered to be a continuation of an ancient alluvial ecosystem, which at the moment is severely damaged.

character, structure and distinctive features of the territory

Lido is a mosaic of the succession of anthropogenic and “natural” biotopes starting from bare concrete up to the old-growth shade alluvial forest. Construction activities have enriched the local landscape by biotopes which would not naturally occur here - "spaces" under bridges, backfills and a diverse mixture of wooden plants in allotment gardens.

general recommendations and strategy of the case for former Lido

• revitalization of riverbanks and renovation of hydrological regime

Lido’s current hydrological situation is sad in comparison with its historical status. The Danube’s side branches were filled in; pools no longer exist; and the natural riverside vegetation was destroyed due to the artificial regulation of the banks. The only option (although probably not realistic) is the revitalization of the riverbanks and the restoration of pools and at least a section of the filled-in branch. However, we are moving towards a gradual shift of the present communities towards drier types - oak-hornbeam forests and subxerophilic grasses.

• intervention-free regime in alluvial forests

The alluvial forest is represented by several types of growth - from the “old-growth” sections up to the heavily visited park nature. However, maintaining segmented forest floors and retaining dead wood, including tree trunk torsos which serve as dens, are essential. This in fact is an intervention-free regime; increased park landscaping in an alluvial forest is absolutely the wrong approach.

• care for solitary wooded plants and old cultural riverside landscape

Aside from species diversity, Lido also has an extremely rugged landscape. This ruggedness has many levels and layers, including the incidence of solitary wooded plants, which reflects the oldest preserved history of this territory and in several places, it most probably represents a relic of the “ancient” cultural riverbank landscape, in particular, massive specimens of Quercus robur, Populus alba andFraxinus excelsior. This layer is essential for Lido’s biological value and genius loci and it should be actively cared for (for example by replacing dead trees).

• ephemeral biotopes

Temporary, ephemeral biotopes represent an essential part of the biodiversity of the territory; however, their protection or conservation is difficult to grasp and frequently difficult to implement. Therefore, in general it is necessary to avoid additional sowing and artificial “greening” and to leave certain sections of Lido accessible to mechanical disturbance, such as cyclocross playgrounds and various small areas that cannot be specified.

• transformation of extinct allotment gardens

The bizarre landscape created by abandoning the allotment gardens is ideal “material” for the creation of unusual forms of extensive parks. The garden cultures, fruit trees and structure of the plots are mixed with an expanding riverbank system and creates a unique biological and landscape mixture. It is essential to avoid the destruction and bulldozing of such territories and instead to provide sensitive “punk” interventions and thus make the entire structure gradually accessible.

• what to do with invasive species?

The entire Lido territory is significantly affected by plant invasions. In addition to common invasive species, less obvious examples are also found (for example Celtis occidentalis); it is estimated that one third of the local flora consists of neophytes and they cover more than half of the entire vegetation cover. However, intervening against invasive species is not recommended as due to the character of this territory (near the river, main roads, extensive allotment gardens) the invasive species will most probably never disappear.

Instead, the handling of invasive species should consist of the proper biological management of biotopes in which certain invasive species are not desirable. This pertains to the mowing of cultural lawns, the regular mechanical disturbing of subxerophile biotopes and the restoration of a hydrological regime of drying alluvial biotopes.

Massive specimen of Populus nigra, massive growth of Clematis vitalba - "old-growth forest interior" of polygon No. 43

High brownfield in unused running polygon – dominated by Artemisisa vulgaris. Polygon No. 51.

Grapevine -Vitis vinifera – one of four dominant species of creepers in deserted allotment gardens. Polygon 32.

Oak-hornbeam fragment in polygon 13.

One of few semi-natural sections of the Danube riverside created by the erosion of artificial regulations. Polygon 44.

Parietaria officinalis, Mediterranean species of nitrophile locations, extensive wild growth.

Chenopodium botrys, rarer plant of early succession in polygon No. 1.

Occasional pools with subhalophile banks, polygon No.1. Obviously, this biotope is used by water birds.

Sporadic vegetation under the bridges is a new and very specific biotope, vegetation cannot grow in the driest and most shaded sections.

Kochia laniflora in polygon 1 – most precious plant species in Lido.

Small pool with fragments of marsh vegetation in polygon No. 49.

Pothead pool in alluvial forest, polygon No. 26.

Southern edge of the pile in polygon No. 11, covered by thermophilic plants.

Interior of the Janko Král Garden – an example of how not to landscape the Lido territory.

Helianthus tuberosus on the edge of the allotment gardens – common invasive plant here.

Map showing the age of biotopes. The lighter biotopes are the youngest, the dark red biotopes are more than 70 years old. The discolored sections are closed up sites.

Significant Species of Plants

· Ambrosia artemisifolia – invasive North-American species which is extremely widespread in this territory. It grows in open, gravel biotopes in the early stage of succession.

· Artemisia annua - polygons 1 and 22;

· Atriplex prostrata – subhalophile species, a small population is situated in polygon 1

· Celtis occidentalis - North-American wooded plant which is cultivated in Europe as decorative and resilient urban wooded plant; it grows wild in the lower tree floor of the alluvial forest

· Chenopodium botrys - polygon 1

· Geranium rotundifolium – introduced Mediterranean species, a relatively abundant population is situated in polygon 39

· Impatiens glandulifera – well-known, originally Himalayan invasive species, occurring in forest clearings throughout the entire territory. Visible, but a relatively harmless invasive plant.

· Iva xanthifolia - only a single specimen in polygon 1

· Kochia laniflora – only in the central section of polygon 1; protected by law in Slovakia

· Linaria genistifolia – scarce in open biotopes in polygons 11,34 and 37

· Parietaria officinalis - Mediterranean species, it grows practically throughout the entire territory here

· Perovskya abrotanoides – Central Asian species, grows wild in polygon 37

· Physalis alkekengi –growing wild in places, massive population in the meadows in the eastern section of polygon 43

· Reynutria japonica – commonly occurring invasive plant. Its hybrid species Reynoutria x bohemica is probably also found in the Lido territory

· Senecio inaquidens – South-African migrant, relatively rare in Slovakia. One specimen was found here in polygon 34

· Xanthium albinum – occurrence of two small populations in riverside growth in polygons 46 and 27

Polygon No. 22 - fragment of old alluvial landscape with ruderal plant communities on successively young surface

Valuable small open areas with incidence of Artemisia annua and Ambrosia artemisifolia.

Solitary oak dub as a residue of the old alluvial landscape, polygon 33.

Concrete surfaces with primitive soil vegetation, polygon 39.

View of one of alluvial clearings in polygon 43, totally overgrown by a mixture of blackberries and Celmatis vitalba.

More distinctive “meadow” enclave with hints of hydrophobic vegetation, eastern edge of polygon No. 43

Physalis alkekengi, massively wild growth in polygon 43.

Succession of hard riverside system with dominating Populus alba, polygon 45.

Specimen of Yucca filamentosa growing wild in polygon 13.

Eastern edge of the territory with obvious sand embankments – the alluvial dynamics on the banks of Danube have not been completely lost.

Intensive invasion of Solidago gigantea and Ailanthus altissima in the spaces vacated after former gardens - polygon No. 18.

Interior of the riverside system with obvious segmented vegetation floors; the shrubbery floor is dominated by Cornus sanguinea.

Massive growth of Reynoutria japonica by the gas station.

Young soft riverside system on the Danube bank with fresh sand embankments and mixture of Populus alba and Salix fragilis, polygon No. 44.

Perovskya abrotanoides growing wild in polygon No. 37.